Differences in symptom occurrence, severity, and distress ratings between patients with gastrointestinal cancers who received chemotherapy alone or chemotherapy with targeted therapy

Introduction

Gastrointestinal (GI) cancers include the esophagus, stomach, small intestine, large intestine (colon), gall bladder, liver, pancreas, rectum, and anus. While the mortality rates for colon and rectal cancers have decreased over the past two decades, other GI cancers (e.g., pancreas) that do not have reliable screening methods have not seen similar effects (1). The American Cancer Society estimates that 304,930 new cases of GI cancers will be diagnosed in 2016 and approximately half of these patients will die from their disease (1).

Historically, chemotherapy (CTX) was one of the standard treatments for GI cancers (2-8). These agents are administered to reduce tumor burden, decrease tumor-related symptoms, improve patients’ well-being, and prolong survival (9-12). However, these agents are inherently toxic and destroy rapidly dividing cancer cells, which results in significant symptoms (3,13). Therefore, ongoing assessments of patients with GI cancers are critical because unrelieved symptoms may alter their CTX regimen, as well as have negative effects on their functional status and quality of life (QOL) (14).

Today, patients with GI cancers are treated with surgery, radiation therapy, CTX, and/or targeted therapy (TT) depending on the stage of their disease at the time of diagnosis (15-18). Because TT was developed to act on well-defined targets or biological pathways, initial evidence suggested that patients tolerated targeted therapies better than traditional CTX (19). In addition, survival rates increased in patients with GI cancers who received TT (20). However, more recent evidence suggests that these targeted therapies result in unique toxicities (e.g., skin changes) (21).

To date, the majority of symptom management research has evaluated patients who were heterogeneous with respect to their cancer diagnoses. Most studies that evaluated the symptom experience of patients with GI cancers were done within the context of randomized clinical trials (RCTs) for new CTX regimens. The evaluation of symptoms within the context of these RCTs is limited because most studies used the National Cancer Institute’s (NCI’s) Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) (22-26). Only four studies used valid and reliable symptom assessment instruments to evaluate various dimensions of the symptom experience (i.e., occurrence, severity, distress) in patients with GI cancers receiving CTX (27-30).

In the first study (28), data from the Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance (CanCORS) study (i.e., a demographically representative national database) were used to describe the prevalence and severity of symptoms in patients who were four to 6 months post diagnosis of lung cancer or colorectal cancer (CRC). Of the 5,422 patients who completed the symptom survey, 93.5% reported at least one symptom in the four weeks before the survey. In addition, 51% reported at least one symptom as moderate or severe. Patients with CRC reported significantly fewer symptoms than patient with lung cancer. In addition, patients who were most recently diagnosed with lung cancer and CRC were more likely to report a significantly higher number of symptoms regardless of the stage of their disease. While this study’s sample was large and representative, comparisons were not made between CRC patients who received CTX with or without TT.

In the second study (29), multiple dimensions of the symptom experience (i.e., occurrence, severity, and distress) associated with the second or third cycle of CTX for CRC were evaluated. On average, these patients (n=104) reported 10.3 (±7.7) symptoms. The five most common symptoms were numbness/tingling in the hands/feet (64%), lack of energy (62%), feeling drowsy (49%), nausea (45%), and shortness of breath (43%). Using the Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale (MSAS), these patients reported higher scores for frequency than for either severity or distress. Again, this study did not evaluate for differences in the symptom experience of CRC patients who received CTX with or without TT.

In a study that evaluated multiple symptoms using the MSAS, as well as psychological distress, social support, and QOL in newly diagnosed patients with GI cancers (n=146) (27), the most common symptoms were fatigue (63%), pain (42.1%), weight loss (41.1%), dry mouth (38.4%), and lack of appetite (35.6%). These patients’ mean anxiety score was 40.5 (±11.2) and 27.4% of the patients were categorized as clinically depressed. While, multiple dimensions of the symptom experience were evaluated, comparisons were not made between GI patients who received CTX with or without TT.

Only one retrospective, cohort study evaluated the symptom experience of patients with GI cancers on targeted therapies (30). In this study, differences in the symptom burden of patients with CRC who received second-line treatments that contained bevacizumab or cetuximab with or without CTX were evaluated. Regardless of treatment group, fatigue was the most common symptom (67%) that occurred at moderate to severe levels. However, compared to bevacizumab, cetuximab produced a significantly higher rate of moderate to severe dry skin (P<0.0001), itching (P=0.0028), and rash (P<0.0001). Of note, compared to the bevacizumab group, patients who received only CTX had a higher rate of moderate to severe nausea (P=0.0485) and tended to report a higher rate of physical pain (P=0.0564). In this study, the Patient Care Monitor Instrument was used to evaluate the severity of 80 symptoms (86 for women), using a 0 to 10 scale. While 80 to 86 symptoms were evaluated, detailed information on the severity and distress of these symptoms were not reported.

Current evidence suggests that approximately 28% of patients with GI cancers will receive TT because of the associated increases in survival (31). Given the paucity of research on the symptom experience of these patients, the purpose of this study was to evaluate for differences in symptom occurrence rates, as well as in severity and distress ratings, in the week following the administration of CTX, between patients with GI cancers who received CTX alone or CTX with TT. We hypothesized that patients who received CTX with TT would report lower symptom occurrence rates, as well as lower severity and distress ratings.

Methods

Patients and settings

This study is part of a larger descriptive, longitudinal study of the symptom experience of oncology outpatients who received CTX (32,33). Eligible patients were ≥18 years of age; had a diagnosis of breast, GI, lung, or gynecological cancer; had received CTX within the preceding four weeks; were scheduled to receive at least two additional cycles of CTX; were able to read, write, and understand English; and provided informed consent. Patients were recruited from two Comprehensive Cancer Centers, one Veterans Affairs hospital, and four community based oncology programs.

A total of 2,234 patients were approached and 1,343 consented to participate (60.1% response rate) in the larger study. The major reason for refusal was being overwhelmed with their cancer treatment. For this study, only patients with GI cancers were included (n=404).

Study procedures

The study was approved by the Committee on Human Research at the University of California at San Francisco and by the Institutional Review Board at each of the study sites. A research staff member in the infusion unit approached eligible patients and discussed participation in the study. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients. Based on the length of the CTX cycle, GI cancer patients completed questionnaires in their homes, a total of six times over two cycles of CTX, namely: before CTX administration (i.e., recovery from previous CTX cycle, Times 1 and 4), approximately one week after CTX administration (i.e., acute symptoms, Times 2 and 5), and approximately two weeks after CTX administration (i.e., potential nadir, Times 3 and 6). For this study, symptom data from the Time 2 assessment were analyzed.

Instruments

A demographic questionnaire obtained information on age, gender, ethnicity, marital status, living arrangements, education, employment status, and income. Functional status was assessed using the Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) scale, which is widely used in patients with cancer and has well established validity and reliability. Patients rated their functional status using the KPS scale that ranged from 30 (I feel severely disabled and need to be hospitalized) to 100 (I feel normal; I have no complaints or symptoms) (34).

Self-Administered Comorbidity Questionnaire (SCQ) consists of 13 common medical conditions simplified into language that can be understood without prior medical knowledge (35). Patients indicated if they had the condition; if they received treatment for it (proxy for disease severity); and if it limited their activity (indication of functional limitations). For each condition, patients can receive a maximum of 3 points. The total SCQ score ranges from 0 to 39. The SCQ has well established validity and reliability (35).

Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) is a 10-item questionnaire that assesses alcohol consumption, alcohol dependence, and the consequences of alcohol abuse in the last 12 months. The AUDIT gives a total score that ranges between 0 and 40. Scores of ≥8 are defined as hazardous use and scores of ≥16 are defined as use of alcohol that is likely to be harmful to health (36,37). The AUDIT has well established validity and reliability (38-40). In this study, its Cronbach’s alpha was 0.63.

A modified version of the MSAS was used to evaluate the occurrence, severity, and distress of 38 symptoms commonly associated with cancer and its treatment. In addition to the original 32 MSAS symptoms, the following six symptoms were assessed: hot flashes, chest tightness, difficulty breathing, abdominal cramps, increased appetite, and weight gain. The MSAS is a self-report questionnaire designed to measure the multidimensional experience of symptoms. Patients were asked to indicate whether they experienced each symptom within the past week (i.e., symptom occurrence). If they experienced the symptom, they were asked to rate its severity and distress. Severity was rated using a 4-point Likert scale (i.e., 1= slight, 2= moderate, 3= severe, 4= very severe). Distress was rated using a 5-point Likert scale (i.e., 0= not at all, 1= mild, 2= moderate, 3= severe, 4= very severe) (41). The validity and reliability of the MSAS are well established (41-43).

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS Version 22 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) and Stata Version 14 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX). Descriptive statistics as means and standard deviations (SD) for quantitative variables and frequencies and percentages for categorical variables were calculated for all study variables. Patients were dichotomized into individuals who received CTX alone or CTX with TT. Independent sample t-tests, Mann-Whitney U tests, and Chi-Square analyses were used to evaluate for differences in demographic and clinical characteristics between the two treatment groups.

Binary logistic regression analyses were performed to test for differences in symptom occurrence rates between the two treatment groups. Ordinal logistic regression analyses were used to test for differences in severity and distress ratings between the two treatment groups (44). Because some of the symptoms had a low occurrence rate, regression analyses were performed only when ≥60 responses were available. Additionally, symptom severity and distress ratings were not analyzed if <15 responses were available in the upper two categories. Because the severity and distress ratings were ordinal and most were highly skewed, analyses for these items were carried out with ordinal logistic regression and estimation was carried out with a nonparametric bootstrap, with 1,000 repetitions for each analysis, to obtain bias-corrected confidence intervals (CI) for the predictors. For each bootstrapped regression, likelihood ratio deviance tests were used to determine whether a set of six covariates that differed between the treatment groups (i.e., age, time since cancer diagnosis, number of metastatic sites including lymph node involvement, number of prior cancer treatments, GI cancer diagnosis, CTX treatment regimen) improved the fit of the model over the single treatment predictor. Significance was evaluated using bias-corrected bootstrapped CIs. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Differences in demographic characteristics between patients who received CTX with or without TT

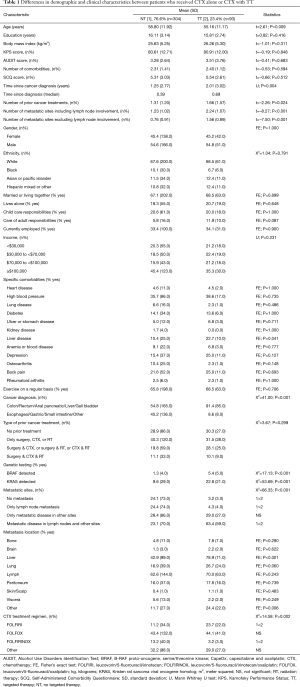

Of the 404 patients with GI cancers who consented to participate, 397 patients (94%) completed the MSAS. Of these 397 patients, 23.4% (n=93) received CTX with TT and 76.6% (n=304) received only CTX. As shown in Table 1, except for age, no differences were found in any demographic characteristics between patients who received CTX alone or CTX with TT. Patients who received CTX with TT were significantly younger (P=0.009).

Full table

Differences in clinical characteristics between patients who received CTX with or without TT

As shown in Table 1, compared to patients who received CTX alone, patients who received CTX with TT were diagnosed with cancer longer (P=0.004) and had a higher number of prior treatments (P=0.024). In addition, a higher percentage of patients on CTX with TT had metastatic disease, specifically to the liver (P<0.001), had a diagnoses of anal, colon, rectum or CRC (P<0.001), and were positive for detection of B-Raf proto-oncogene, serine/threonine kinase (BRAF) and Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog (KRAS) mutations (both P<0.001).

The percentages of patients who received the most common CTX regimens differed between the two groups (P=0.002). In patients who received CTX alone, the most common CTX regimens were: leucovorin/5-fluorouracil/irinotecan (FOLFIRI), leucovorin/5-fluorouracil/oxaliplatin (FOLFOX), capecitabine and oxaliplatin (CapeOX), gemcitabine and paclitaxel, and leucovorin/5-fluorouracil/irinotecan/oxaliplatin (FOLFIRINOX). In patients who received targeted therapies, the most common CTX regimens were: FOLFIRI, FOLFOX, FOLFIRINOX, and CapeOX. The most common targeted therapies were: bevacizumab (80.4%), cetuximab (12.4%), panitumumab (6.2%), and transtuzumab (1.0%).

Differences in symptom occurrence rates and total number of symptoms between patients who received CTX with or without TT

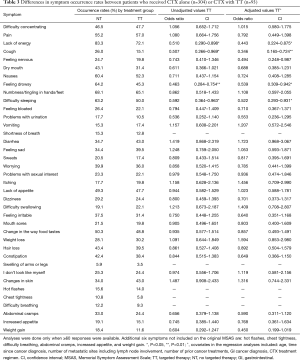

The occurrence rates for the top ten symptoms are listed in Table 2. No differences were found in the total number of symptoms reported between patients who received CTX with ( =11.50±6.9) or without (

=11.50±6.9) or without ( =12.75±6.8; t=1.501, P=0.134) TT. The five symptoms with the highest occurrence rates in patients who received CTX with TT were: lack of energy (72.1%), numbness/tingling in hands or feet (65.1%), pain (57.0%), nausea (52.3%), and difficulty sleeping (50.0%). Except for pain, four of these symptoms were in the top five symptoms reported by the patients who received CTX alone.

=12.75±6.8; t=1.501, P=0.134) TT. The five symptoms with the highest occurrence rates in patients who received CTX with TT were: lack of energy (72.1%), numbness/tingling in hands or feet (65.1%), pain (57.0%), nausea (52.3%), and difficulty sleeping (50.0%). Except for pain, four of these symptoms were in the top five symptoms reported by the patients who received CTX alone.

Full table

In the bivariate analyses (Table 3), patients who received CTX with TT reported lower occurrence rates for lack of energy, cough, feeling drowsy, and difficulty sleeping (all, P<0.05). In the multivariable analyses that adjusted for age, time since cancer diagnosis, number of metastatic sites including lymph node involvement, number of prior cancer treatments, GI cancer diagnosis, and CTX treatment regimens, patients who received CTX with TT reported significantly lower occurrence rates for lack of energy (P<0.05), cough (P<0.01), feeling drowsy (P<0.05), and difficulty sleeping (P<0.05).

Full table

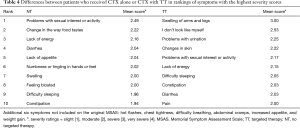

Differences in symptom severity scores between patients who received CTX with or without TT

The ten symptoms with the highest mean severity scores are listed in Table 4. For patients who received CTX with TT, the five symptoms with the highest severity scores were: swelling of arms and legs, “I don’t look like myself”, problems with urination, changes in skin, and problems with sexual interest or activity. For patients who received CTX alone, the five symptoms with the highest severity scores were: problems with sexual interest or activity, change in the way food tastes, lack of energy, diarrhea, and lack of appetite.

Full table

In the bivariate analyses (Table 5), patients who received CTX with TT reported a lower severity score for change in the way food tastes (P=0.023). However, these patients reported significantly higher severity scores for “I don’t look like myself” (P=0.005), and changes in skin (P=0.019). In the multivariable analyses, the severity scores for dry mouth (P=0.034), and change in the way food tastes (P=0.035) were significantly lower in patients who received CTX with TT. In addition, these patients were more likely to report higher severity scores for “I don’t look like myself” (P=0.026).

Full table

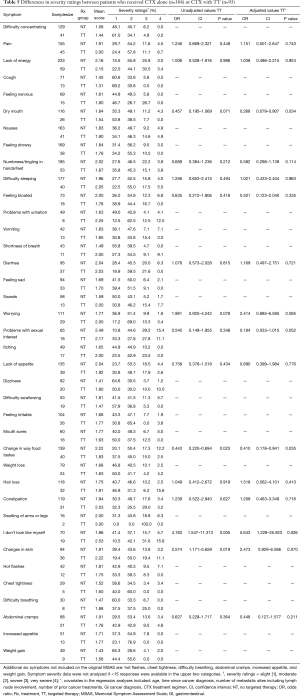

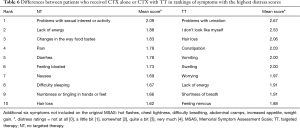

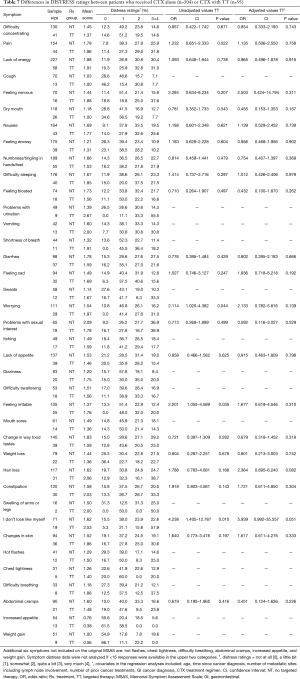

Differences in symptom distress scores between patients who received CTX with or without TT

The ten symptoms with the highest distress scores are listed in Table 6. For patients who received CTX with TT, the five symptoms with the highest distress scores were: problems with urination, “I don’t look like myself”, hair loss, constipation, and vomiting. For patients who received CTX alone, the five symptoms with the highest distress scores were: problems with sexual interest or activity, lack of energy, change in the way food tastes, pain, and diarrhea.

Full table

In the bivariate analyses (Table 7), patients who received CTX with TT reported significantly higher distress ratings for: worrying (P=0.044), feeling irritable (P=0.035), and “I don’t look like myself” (P=0.010). In the multivariable analyses, none of these between group differences remained significant.

Full table

Discussion

This study is the first to report on differences in multiple dimensions of the symptom experience in patients with GI cancers who received CTX with or without TT. Like the current literature, which reports conflicting evidence on the side effects associated with TT (45), our a priori hypothesis was only partially supported. Depending on the dimension evaluated, some symptoms were better and some were worse in patients on TT. Of note, in all of the multivariate analyses, neither GI cancer diagnosis nor CTX treatment regimen was a significant predictor of any symptoms’ occurrence, severity or distress.

Symptom occurrence

While fatigue is the most common symptom reported by oncology patients receiving CTX (46), compared to previous reports of newly diagnosed patients with GI cancers (63%) (27), and CRC patients receiving CTX (62.0%) (29), the overall occurrence rate for fatigue (i.e., lack of energy) in our study regardless of treatment group was higher (80.7%). This difference may be related to differences in age, GI cancer diagnoses, and/or presence of metastatic disease. However, compared to patients who received CTX alone, patients on TT had a 55.7% decrease in the odds of reporting fatigue.

In terms of the overall occurrence rates for feeling drowsy and difficulty sleeping, our findings are similar to those of Pettersson and colleagues who reported occurrence rates of 49.0% and 46.0%, respectively for these two symptoms (29). Again, when differences in the occurrence rates for both of these symptoms were evaluated, patients in our study on TT had a 46.1% and 47.8% decrease in the odds of reporting feeling drowsy and difficulty sleeping, respectively. These differences in rates for all three symptoms remained significant after controlling for age, time since cancer diagnosis, number of metastatic sites, number of prior cancer treatments, GI cancer diagnosis, and CTX regimen.

While the exact reasons for the decreased occurrence rates for fatigue, feeling drowsy, and difficulty sleeping in patients on targeted therapies are not known, a number of potential explanations warrant consideration. First, while it is possible that specific CTX regimens and/or administration schedules could result in different occurrence rates for fatigue, no evidence was found to support this hypothesis, after we controlled for CTX regimen in the multivariate analyses. In addition, in a recent meta-analysis that evaluated the effects of doublet versus single cytotoxic agent treatment for non-small cell lung cancer (47), no between group differences in fatigue occurrence rates were found. Finally, fatigue, feeling drowsy, and sleep disturbance were reported in previous studies to be part of a symptom cluster (48,49). Given that all three symptoms had higher occurrence rates in the patients who received only CTX suggests that when these three symptoms do occur they may interact with each other and result in a higher symptom burden.

The occurrence of cough in our study was similar to previous reports that ranged from 15.8% (27) to 28.0% (29). Of note, while the overall occurrence rate for cough was relatively low in our study (i.e., 23.5%), patients on TT had a 65.4% decrease in the odds of reporting cough. While the occurrence of comorbid lung disease or lung metastasis was similar in both treatment groups, the occurrence rate for esophageal cancer was higher in the CTX alone group (6.6%) compared to the TT group (3.5%). Given that esophageal cancer is associated with gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD) and chronic cough is a common symptom in patients with GERD (50), the differential occurrence rates for cough may be partially explained by the different rates of esophageal cancer in the two treatment groups.

Symptom severity

None of the symptoms that had significant between group differences in occurrence rates had differences in severity scores. However, the severity scores for dry mouth and change in the way food tastes were significantly lower in the TT group. For the total sample, mean severity scores for dry mouth (i.e., 1.79) and change in the way food tastes (i.e., 2.12) were similar to those reported by Yan and colleagues (i.e., 1.66 and 2.29, respectively) (27). However, when treatment group differences in the severity rates for both of these symptoms were evaluated, patients on TT were 73.2% and 59.0% less likely to report a higher severity score for dry mouth and change in the way food tastes, respectively.

Consistent with previous studies (51,52), patients receiving CTX experience significant changes in the way food tastes and dry mouth, that peak after the administration of CTX. In addition, in another study (53), the severity of these two symptoms were moderately correlated (r=0.425, P≤0.01). However, no studies were identified that evaluated the severity of these two symptoms in patients on TT. Most of the previous studies of TT used the CTCAE scoring criteria, which only evaluates “mucositis/stomatitis” (54,55). In both treatment groups, the severity scores for taste changes and dry mouth were in the moderate range. Because these two symptoms can interfere with food and fluid intake, both groups of patients warrant ongoing assessments to evaluate for and manage nutritional deficits (56).

While patients on TT reported lower severity scores for change in the way food tastes and dry mouth, these patients reported a higher severity score for “I don’t look like myself”. Patients on targeted therapies were 5.6 times more likely to report a higher severity score for the symptom “I don’t look like myself”. While the hair loss associated with CTX can impact a patient’s body image (57), the between group differences in this symptom may be directly related to the skin toxicities associated with TT. In one study (58), 41% of patients with advanced CRC treated with TT reported psychological distress caused by a rash. When asked how the rash affected their willingness to go out into public, 25% of the patients answered “somewhat” and 22% answered “very much”. Additional research is warranted using a symptom assessment scale that evaluates specific skin toxicities to determine their impact on the body image of patients who receive targeted therapies.

Symptom distress

While in the bivariate analyses, patients on CTX with targeted therapies reported higher distress scores for worrying, feeling irritable, and “I don’t look like myself”, these differences did not remain significant in the multivariable analyses. Only one study was found that reported mean MSAS distress scores in a sample of Chinese patients receiving treatment for GI cancers (27). The five symptoms with the highest distress scores were sleep disturbance (2.06), change in the way food tastes (1.93), hair loss (1.92), lack of energy (1.82), and shortness of breath (1.79). In our study, except for shortness of breath, patients who received CTX alone reported that the same symptoms were the most distressing and the distress scores were comparable. However, in the patients in our study who received TT, only three of the five most distressing symptoms were similar to those reported by Yan and colleagues (27) (i.e., hair loss, lack of energy, shortness of breath). In fact, the two most distressing symptoms reported by patients on TT (i.e., problems with urination, “I don’t look like myself”) were not listed in the top ten most distressing symptoms by patients who received only CTX in the study by Yan and colleagues (27).

Consistent with previous studies (27,29), in both treatment groups in our study, the symptoms with the highest distress scores did not have the highest occurrences rates or severity scores. An evaluation of symptom distress is important because unrelieved distress can interfere with patients’ willingness to obtain or continue treatment, which can impact overall survival. Our findings suggest that clinicians need to assess multiple dimensions of the symptom experience in patients with GI cancers and attempt to manage the most common, severe, and distressing symptoms.

Conclusions

While significant between groups differences in patients’ symptom experiences were identified, patients in both treatment groups reported an average of 12.5 symptoms during the week following CTX administration. This finding is consistent with previous reports that found that patients who received CTX for CRC (29) and patients with advanced cancer (59) reported between 10.3 and 11.7 symptoms. Therefore, both groups of patients warrant ongoing assessments to optimally manage their unrelieved symptoms.

Several study limitations need to be acknowledged. Information on the cumulative doses of CTX and TT received by these patients prior to enrollment were not collected. Because the multidimensional symptom instrument utilized in the study was not developed to evaluate symptoms experienced by patients receiving TT, additional symptoms that are specific to TT (e.g., pruritis associated with rash, xerosis, pain associated with paronychia) (60) warrant evaluation in future studies. In addition, the varied distribution of GI cancer diagnoses and CTX regimens makes it difficult to distinguish specific symptoms associated with these characteristics. Finally, while the total sample was large, the number of patients on TT was relatively small. Therefore, differences in the symptom burden associated with specific targeted therapies could not be evaluated. Additional differences may emerge in future studies with a larger sample of patients on CTX with TT.

Findings from this study provide new information regarding symptoms experienced by GI cancer patients receiving CTX with and without TT. Clinicians can use this information to better assess and manage symptoms in both treatment groups. Future studies need to evaluate for differences between these two treatment groups in changes over time in occurrence, severity, and distress of these symptoms. These findings will allow for the development and testing of more tailored symptom management interventions.

Acknowledgements

Funding: This study was supported by a grant from the National Cancer Institute (NCI, CA134900). Dr. Christine Miaskowski is an American Cancer Society Clinical Research Professor and is funded by a K05 award from the NCI (CA168960). Mr. Tantoy is funded by a National Institutes of Health (NIH) T32 grant (T32NR007088).

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The study was approved by the Committee on Human Research at the University of California at San Francisco and by the Institutional Review Board at each of the study sites (VCU) (No. 10-02882) and written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

References

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin 2016;66:7-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ouwerkerk J, Boers-Doets C. Best practices in the management of toxicities related to anti-EGFR agents for metastatic colorectal cancer. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2010;14:337-49. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gerber DE. Targeted therapies: A new generation of cancer treatments. Am Fam Physician 2008;77:311-9. [PubMed]

- Antoniou G, Kountourakis P, Papadimitriou K, et al. Adjuvant therapy for resectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma: review of the current treatment approaches and future directions. Cancer Treat Rev 2014;40:78-85. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- O'Reilly EM, Abou-Alfa GK. Cytotoxic therapy for advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Semin Oncol 2007;34:347-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pasini F, Fraccon AP, De Manzoni G. The role of chemotherapy in metastatic gastric cancer. Anticancer Res 2011;31:3543-54. [PubMed]

- Lordick F, Lorenzen S, Yamada Y, et al. Optimal chemotherapy for advanced gastric cancer: is there a global consensus? Gastric Cancer 2014;17:213-25. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ang C, O'Reilly EM, Abou-Alfa GK. Targeted agents and systemic therapy in hepatocellular carcinoma. Recent Results Cancer Res 2013;190:225-46. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ragnhammar P, Hafstrom L, Nygren P, et al. A systematic overviwe of chemotherapy effects in colorectal cancer. Acta Oncol 2001;40:282-308. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Freelove R, Walling AD. Pancreatic cancer: diagnosis and management. Am Fam Physician 2006;73:485-92. [PubMed]

- Stahl M, Budach W, Meyer HJ, et al. Esophageal cancer: Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 2010;21 Suppl 5:v46-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wagner AD, Grothe W, Haerting J, et al. Chemotherapy in advanced gastric cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis based on aggregate data. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:2903-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chabner BA, Roberts TG. Timeline: Chemotherapy and the war on cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2005;5:65-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Siefert ML. Fatigue, pain, and functional status during outpatient chemotherapy. Oncol Nurs Forum 2010;37:E114-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Raichle KA, Osborne TL, Jensen MP, et al. The reliability and validity of pain interference measures in persons with spinal cord injury. J Pain 2006;7:179-86. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Williams VS, Smith MY, Fehnel SE. The validity and utility of the BPI interference measures for evaluating the impact of osteoarthritic pain. J Pain Symptom Manage 2006;31:48-57. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McDermott AM, Toelle TR, Rowbotham DJ, et al. The burden of neuropathic pain: results from a cross-sectional survey. Eur J Pain 2006;10:127-35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gore M, Brandenburg NA, Dukes E, et al. Pain severity in diabetic peripheral neuropathy is associated with patient functioning, symptom levels of anxiety and depression, and sleep. J Pain Symptom Manage 2005;30:374-85. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liu S, Kurzrock R. Toxicity of targeted therapy: Implications for response and impact of genetic polymorphisms. Cancer Treat Rev 2014;40:883-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- El Zouhairi M, Charabaty A, Pishvaian MJ. Molecularly targeted therapy for metastatic colon cancer: proven treatments and promising new agents. Gastrointest Cancer Res 2011;4:15-21. [PubMed]

- Niraula S, Amir E, Vera-Badillo F, et al. Risk of incremental toxicities and associated costs of new anticancer drugs: a meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:3634-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kang BW, Kim TW, Lee JL, et al. Bevacizumab plus FOLFIRI or FOLFOX as third-line or later treatment in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer after failure of 5-fluorouracil, irinotecan, and oxaliplatin: a retrospective analysis. Med Oncol 2009;26:32-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Braun MS, Seymour MT. Balancing the efficacy and toxicity of chemotherapy in colorectal cancer. Ther Adv Med Oncol 2011;3:43-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Boccia RV, Cosgriff TM, Headley DL, et al. A phase II trial of FOLFOX6 and cetuximab in the first-line treatment of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Clin Colorectal Cancer 2010;9:102-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tsutsumi S, Ishibashi K, Uchida N, et al. Phase II trial of chemotherapy plus bevacizumab as second-line therapy for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer that progressed on bevacizumab with chemotherapy: the Gunma Clinical Oncology Group (GCOG) trial 001 SILK study. Oncology 2012;83:151-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tol J, Koopman M, Cats A, et al. Chemotherapy, bevacizumab, and cetuximab in metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med 2009;360:563-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yan H, Sellick K. Symptoms, psychological distress, social support, and quality of life of Chinese patients newly dianosed with gastrointestinal cancer. Cancer Nurs 2004;27:389-99. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Walling AM, Weeks JC, Kahn KL, et al. Symptom prevalence in lung and colorectal cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manage 2015;49:192-202. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pettersson G, Bertero C, Unosson M, et al. Symptom prevalence, frequency, severity, and distress during chemotherapy for patients with colorectal cancer. Support Care Cancer 2014;22:1171-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Walker MS, Pharm EY, Kerr J, et al. Symptom burden & quality of life among patients receiving second-line treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer. BMC Res Notes 2012;5:314. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Siegel R, DeSantis C, Virgo K, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin 2012;62:220-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wright F, D'Eramo Melkus G, Hammer M, et al. Trajectories of evening fatigue in oncology outpatients receiving chemotherapy. J Pain Symptom Manage 2015;50:163-75. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wright F, D'Eramo Melkus G, Hammer M, et al. Predictors and trajectories of morning fatigue are distinct from evening fatigue. J Pain Symptom Manage 2015;50:176-89. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Karnofsky DA, Abelmann WH, Craver LF, et al. The use of the nitrogen mustards in the palliative treatment of carcinoma. Cancer 1948;1:634-56. [Crossref]

- Sangha O, Stucki G, Liang MH, et al. The Self-Administered Comorbidity Questionnaire: a new method to assess comorbidity for clinical and health services research. Arthritis Rheum 2003;49:156-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Babor TF, Higgins-Biddle JC, Saunders JB, et al. AUDIT: The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: Guidelines for Use in Primary Care. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2001.

- Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, Saunders J, et al. AUDIT: The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: Guidelines for Use in Primary Care. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 1992.

- Berks J, McCormick R. Screening for alcohol misuse in elderly primary care patients: a systematic literature review. Int Psychogeriatr 2008;20:1090-103. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Berner MM, Kriston L, Bentele M, et al. The alcohol use disorders identification test for detecting at-risk drinking: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Stud Alcohol Drugs 2007;68:461-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Reinert DF, Allen JP. The alcohol use disorders identification test: an update of research findings. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31:185-99. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Portenoy RK, Thaler HT, Kornblith AB, et al. The Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale: an instrument for the evaluation of symptom prevalence, characteristics and distress. Eur J Cancer. 1994;30A:1326-36. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hung HC, Chien TW, Tsay SL, et al. Patient and clinical variables account for changes in health-related quality of life and symptom burden as treatment outcomes in colorectal cancer: A longitudinal study. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013;14:1905-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Browall M, Kenne Sarenmalm E, Nasic S, et al. Validity and reliability of the Swedish version of the Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale (MSAS): An instrument for the evaluation of symptom prevalence, characteristics, and distress. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013;46:131-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Singer JD, Willett JB. Applied longitudinal data analysis: Modeling change and event occurence. 1st ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2003.

- Dy GK, Adjei A. Understanding, recognizing, and managing toxicities of targeted anticancer therapies. CA Cancer J Clin 2013;63:249-79. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Butt Z, Rosenbloom SK, Abernethy AP, et al. Fatigue is the most important symptom for advanced cancer patients who have had chemotherapy. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2008;6:448-55. [PubMed]

- Qi WX, Tang LN, He AN, et al. Doublet versus single cytotoxic agent as first-line treatment for elderly patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lung 2012;190:477-85. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ho SY, Rohan KJ, Parent J, et al. A longitudinal study of depression, fatigue, and sleep disturbances as a symptom cluster in women with breast cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage 2015;49:707-15. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liu L, Rissling M, Natarajan L, et al. Relationship between fatigue and sleep in cancer. Brain Behav Immun 2012;26:706-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hopper AD. Improving the diagnosis and management of GORD in adults. Practitioner 2015;259:27-32. [PubMed]

- Ohrn KEO, Wahlin Y-B, Sjoden P-O. Oral status during radiotherapy and chemotherapy: a descriptive study of patient experiences and the occurrence of oral complications. Support Care Cancer. 2001;9:247-57. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rehwaldt M, Wickham R, Purl S, et al. Self-care strategies to cope with taste changes after chemotherapy. Oncol Nurs Forum 2009;36:E47-E56. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Epstein JB, Phillips N, Parry J, et al. Quality of life, taste, olfactory and oral function following high-dose chemotherapy and allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant 2002;30:785-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Grothey A, Cutsem EV, Sobrero A, et al. Regorafenib monotherapy for previously treated metastatic colorectal cancer (CORRECT): an international, multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2013;381:303-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Meyerhardt JA, Stuart K, Fuchs CS, et al. Phase II study of FOLFOX, bevacizumab and erlotinib as first-line therapy for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Ann Oncol 2007;18:1185-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hutton JL, Baracos VE, Wismer WV. Chemosensory dysfunction is a primary factor in the evolution of declining nutritional status and quality of life in patients with advanced cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage 2007;33:156-65. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rosman S. Cancer and stigma: experience of patients with chemotherapy-induced alopecia. Patient Educ Couns. 2004;52:333-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Romito F, Giuliani F, Cormio C, et al. Psychological effects of cetuximab-induced cutaneous rash in advanced colorectal cancer patients. Support Care Cancer 2010;18:329-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chang VT, Scott CB, Gonzalez ML, et al. Patient-reported outcomes for determining prognostic groups in veterans with advanced cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage 2015;50:313-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lacouture ME, Mitchell EP, Piperdi B, et al. Skin toxicity evaluation protocol with panitumumab (STEPP), a phase II, open-label, randomized trial evaluating the impact of a pre-emptive skin treatment regimen on skin toxicities and quality of life in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:1351-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]