Survival benefits of palliative gastrectomy in stage IV gastric cancer: a propensity score matched analysis

Introduction

Gastric cancer is the fifth most common cancer worldwide (1), and adenocarcinomas account for the majority of the histological type. In the United States, more than one third of all newly diagnosed gastric cancer cases are of stage IV with metastasis to distant sites. Although great advances in chemotherapy and targeted therapy have improved survival, the overall prognosis remains very poor based on data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) statistics (2).

Based on the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines, chemotherapy with or without trastuzumab is the first line of care for gastric cancer with distant metastasis. Palliative gastrectomy is usually reserved for patients with potentially life-threatening complications such as gastrointestinal bleeding, perforation or obstruction. However, it is also performed in addition to chemotherapy in patients with a single non-curable metastasis confined to either the liver, peritoneum, or para-aortic lymph node. However, the randomized controlled trial (RCT) failed to demonstrate any survival benefits of gastrectomy and chemotherapy compared with chemotherapy alone (3). A systematic review and meta-analysis of 14 studies on 3,003 incurable advanced gastric cancer patients revealed that palliative gastrectomy is associated with a significant improvement in the overall survival (HR =0.56; 95% CI: 0.39–0.80; P<0.002) (4). However, other smaller retrospective studies have yielded inconclusive findings (5-11). Although additional prospective RCTs are needed to clarify this issue, reasonable evidence derived from real-world clinical data can be useful if the confounding factors are well controlled and can guide clinical practice (12).

The newly released SEER database has information on the pathology, treatment, and survival for thousands of malignant tumors including gastric cancers diagnosed in the United States from 1975 to 2016, covering approximately 28 percent of the US population. We employed these real-world data to analyze the effects of palliative gastrectomy on the overall survival in patients with stage IV gastric adenocarcinoma.

Methods

Database and variables

Records of metastatic stomach cancer diagnosed from 2010 to 2016 were downloaded from the SEER database (Incidence - SEER 18 Regs Custom Data, Nov 2018 submission) with due permission, using the SEER*Stat software version 8.3.5 (National Cancer Institute, USA). The downloaded data included information on (I) patient demographics including age, sex, race, state-country, and marital status at diagnosis, (II) tumor pathology including the primary tumor site, size, extension, histological type and behavior according to the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology (ICD-O-3), and (III) tumor spread and staging. The SEER-18 database not only incorporated the TNM stage based on the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) seventh edition staging criteria in 2010 but also used the Collaborative Stage Data Set as a supplement. Since 2004, for patients with advanced disease at diagnosis (stage IV), the variable “CS Mets at DX” gives information on whether metastasis was confined to distant lymph node(s) or spread to distant site(s) with /without lymph node(s) (codes 10, 40 and 50, respectively). Code 60 indicates M1 with no information on distant metastasis. More importantly, for cases uploaded in 2010 and later, the variables “CS Mets at Dx-Bone, -Liver, -Lung and -Brain” indicate the specific sites of metastasis (4). Additionally, brief information regarding therapies is from available from the variables “RX Summ-Surg Prim Site (1998+)” (surgery for the primary tumor), and “RX Summ-Surg Oth Reg/Dis (2003+)” (surgical procedure for resection of distant lymph node(s), other tissue(s) or organ(s) beyond the primary site). The custom database also includes information on whether chemotherapy or radiotherapy was given to the patients (5). The survival time and vital status were used for the survival analysis.

Record selection

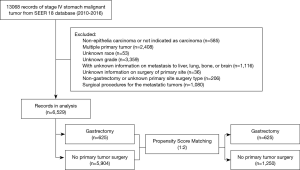

In the SEER database, information on metastasis to specific site(s) became available only in 2010. And therefore, the selected records covered only cases diagnosed between 2010 and 2016. The included records were related to (I) primary stomach malignant tumors (ICD-O-3/WHO 2008 primary sites code C16.0-C16.9), (II) stage IV disease in the derived AJCC Stage Group, 7th ed., (III) tumors histologically indicated as epithelia carcinomas, i.e., ICD-O-3 histologic type/behavior code 8010/3-8579/3, and (IV) patients who underwent gastrectomy and no other cancer-directed surgical procedure at the primary site. Records related to (I) histological codes indicating non-epithelia carcinomas, such as complex mixed and stromal neoplasms, (II) patients with multiple primary cancers, and (III) patients who underwent local tumor destruction or excision (photodynamic therapy, electrocautery, cryosurgery, or laser ablation) were excluded from the study. Since variables with missing values cannot be incorporated for propensity score matching (PSM) analysis, records with missing values for “age at diagnosis”, “sex”, “race”, “primary site”, “grade”, “CS mets at DX-bone/brain/liver/lung (2010+)”, and “RX Summ-Surg Oth Reg/Dis (2003+)”, as well as those with no information on distant lymph node metastasis at diagnosis were also excluded. Figure 1 shows the flowchart of case selection.

Transformation of the variables

For the purpose of analysis, some polytomous variables in the data set were transformed. For the “primary site” variable, tumors located in the fundus of the stomach, body of the stomach, gastric antrum, pylorus, lesser or greater curvature of the stomach were re-classified as a non-cardia tumor. Tumor location was re-classified as “cardia”, “non-cardia”, “overlapping lesions” and “stomach, NOS”. In terms of “grade”, well and moderately differentiated tumors were merged as (G1/2), while poorly differentiated and undifferentiated (G3-4) tumors were merged as G3/4. Since adenocarcinomas accounted for the majority of the cases, the histological subtype was re-classified as “adenocarcinoma” and “non-adenocarcinoma”. The continuous variable “age at diagnosis” was also transformed into a categorical variable. The X-tile plotting software was used to determine the cut-off value for the continuous variables in terms of their effect on survival (13). Based on this analysis, survival curves were separated into 3 age groups divided by 2 cut-off points: 65 and 80 years. Age was, therefore, presented as 3 subgroups: “<65 years”, “65–79 years” and “≥80 years”.

Statistical analysis

Frequency and percentages were used to describe the categorical variables. The Chi-square test was used to determine the distribution of the categorical clinical and pathological variables between the groups. Survival curves were generated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and the Log-rank test was used to assess the difference between the survival curves. Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression was applied to evaluate the effects of gastrectomy on prognosis, and the results were presented as HRs and 95% CIs. We included all clinically significant variables in the multivariable analysis. The above statistical tests and Cox proportional hazards regression were performed using the SPSS 22.0 statistical software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). All P values were 2-tailed, and values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

There were nine times more cases in the no gastrectomy group than in the gastrectomy group (625 vs. 5,904). Significant variations in baseline characteristics, such as age, sex, race, primary tumor location, grade, distant organ/site metastasis and distant metastatic site surgery, existed between the two groups, which may have influenced the prognosis of the patients. PSM was, therefore, used for a more objective comparison (14,15). PSM was performed on the ‘R’ version 3.5.0 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) using the “MatchIt” packages (http://www.r-project.org/). The matching algorithm was the nearest neighbor matching with 1:2 ratio and the caliper was 0.005, the estimation algorithm was logistic regression with age, sex, race, primary tumor location, histological subtype, grade, metastatic organ/site, chemotherapy and radiotherapy as covariates. Enter method was used in the logistic regression. The Chi-square test, Kaplan-Meier survival analysis with log-rank test, and multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression were performed again after PSM using the SPSS Software.

Results

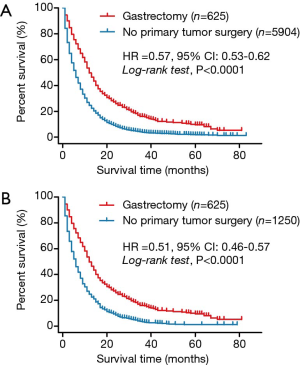

Overall, 13,068 records of stage IV stomach malignant tumors were included in the SEER 18 custom database from 2010 to 2016. Of them, the following were excluded: 585 cases with non-epithelia carcinomas or not indicated as carcinomas, 2,408 diagnosed with multiple primary tumors, 53 of unknown race, 3,359 of unknown grade, 1,116 with no information on metastasis to liver, lung, bone, or brain, 36 with no information on primary tumor surgery, 206 cases with non-gastrectomy or other unknown types of surgery for the primary tumor, and 1,080 cases involving surgical procedures for the metastatic tumors. Finally, a data set containing records for 6,529 patients with stage IV gastric cancer were generated for statistical analysis. Of these, 625 patients had undergone palliative gastrectomy, while the remaining 5,904 did not undergo any cancer-directed surgical procedure for the primary tumor. Figure 1 shows the flowchart for case screening. The Kaplan-Meier survival analysis revealed that the overall crude survival was higher in patients who underwent gastrectomy for the primary tumor than in those who did not (median OS: 12.0 vs. 6.0 months, HR =0.57, 95% CI: 0.53–0.62, log-rank test, P<0.0001). Figure 2A shows the survival curves for the two groups.

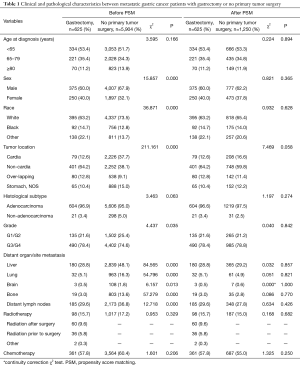

Table 1 summarizes the patient characteristics at baseline in the two groups. The gastrectomy group compared with the no gastrectomy group included more women than men (40.0% vs. 32.1%, P<0.001), and patients with higher grade tumors (78.4% vs. 74.6% for G3/4 tumors, P=0.035). The distribution of race and primary tumor location was also different between the two groups. Compared with the no gastrectomy group, the gastrectomy group had a lower prevalence of metastasis to liver (28.8% vs. 48.1%), lung (5.1% vs. 16.3%), brain (0.5% vs. 1.8%), bone (3.0% vs. 13.6%), and distant lymph nodes (29.6% vs. 36.8%) at diagnosis.

Full table

After performing the 1:2 PSM analysis in R software, 625 cases from the gastrectomy group were matched with 1,250 cases from the no gastrectomy group. These 1,875 cases were then included in the final analysis. Table 1 summarizes the baseline characteristics after PSM. As shown in Figure 2B, the Kaplan-Meier survival analysis revealed that the adjusted overall survival was still higher in the gastrectomy group than in the no gastrectomy group (median OS: 12.0 vs. 6.0 months, HR =0.51, 95% CI: 0.46–0.57, log-rank test, P<0.0001).

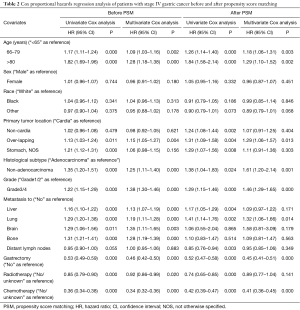

As shown in Table 2, based on the Cox regression analysis of the original dataset, gastrectomy was an independent positive prognostic factor for stage IV gastric cancer patients, with a 47% and 54% decrease in the risk of mortality based on univariate (HR =0.53; 95% CI: 0.49–0.59, P<0.001) and multivariate (HR =0.46, 95% CI: 0.42–0.50, P<0.001) analyses, respectively. While sex and race had no effect on survival, older age at diagnosis increased the risk of mortality. While metastasis to the liver, lung, brain, and bone increased the risk of mortality, metastasis to distant lymph nodes did not. Compared with adenocarcinomas and lower grade (G1/2) tumors, non-adenocarcinomas and higher grade (G3/4) tumors increased the risk of mortality. A higher risk of death was noted in patients with over-lapping lesions than in those with cardia tumors. Both radiotherapy and chemotherapy decreased the risk of mortality. After PSM, Cox regression using the same covariates still demonstrated an increase in survival in patients who underwent gastrectomy (HR =0.45, 95% CI: 0.41–0.51, P<0.001). However, only lung metastasis showed a significant increase in the risk of mortality (HR =1.32, 95% CI: 1.06–1.66, P=0.014). Patients who received chemotherapy but not radiotherapy showed a decrease in the risk of mortality (HR =0.41, 95% CI: 0.36–0.45, P<0.001) (Table 2).

Full table

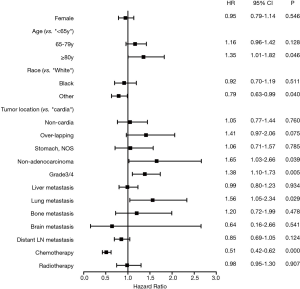

Not all patients with stage IV disease benefitted from palliative gastrectomy. To explore the factors that influence survival in patients undergoing palliative gastrectomy, Cox regression analysis was performed again for the 625 patients’ cohort, and the results were presented as a forest plot (Figure 3). Palliative gastrectomy increased the risk of mortality in patients who (I) were ≥80 years old compared with those <65 years old (HR =1.35, 95% CI: 1.01–1.82, P=0.05), (II) were diagnosed with grade 3/4 non-adenocarcinomas compared with grade 1/2 adenocarcinomas, and (III) had lung metastasis compared with no lung metastasis. However, chemotherapy (HR =0.51, 95% CI: 0.42–0.62, P<0.001), but not radiotherapy (HR =0.98, 95% CI: 0.95–1.30, P=0.907) reduced the risk of mortality in these patients.

Discussion

The current study demonstrates that gastrectomy could decrease the risk of mortality in advanced gastric cancer when compared with no primary tumor surgery. Similar findings have been reported for strictly-selected cases with advanced colorectal and breast cancers (16-19). Primary tumor surgery may reduce the potentially immunosuppressive tumor burden and remove the source of further metastases (20). Palliative primary tumor surgery for some cancers such as renal cell carcinoma is beneficial for metastatic tumor shrinkage and survival of patients (21-23). However, the only randomized clinical trial REGATTA that evaluated the benefits of gastrectomy was also terminated ahead of time due to the negative results from the interim analysis (3). In REGATTA study, about one-third tumors located in upper third of stomach in gastrectomy plus chemotherapy arm, while cardia tumor accounted for only 12.6% in gastrectomy group in our population. A multi-institutional US study demonstrated that long-term outcome was worse among patients with gastric cardia adenocarcinoma (24). This may explain the disappointment results of REGATTA. Similarly, a large cohort analysis with 97,060 gastric cancer patients from National Cancer Database revealed that proximal gastric cancer and distal gastric cancer have different prognosis and tumor location should be taken into consideration when stratifying patients for optimal therapeutic strategies (25). Although primary tumor resection is not recommended for advanced gastric cancer except for patients complicated with urgent or potential fatal events due to the following reasons: (I) the unfavorable biological behavior of gastric cancer compared with breast and colorectal cancer, (II) high incidence of malnutrition after resection of stomach, (III) poor achievements in systemic therapy, and (IV) weak immunosuppressive effects of the primary tumor on metastatic tumors in gastric cancer. However, palliative gastrectomy is still performed in the real-world clinical practice, as revealed by records of hundreds of patients with stage IV gastric cancer who underwent the procedure, in the SEER database.

Since most of the patient and tumor characteristics at baseline were not balanced between the two groups, we decided to perform PSM. However, even after 1:2 matching between the gastrectomy and no gastrectomy groups, the survival was still higher in the gastrectomy group. More importantly, the PSM analysis produced a relatively credible interpretation of the uncontrolled observation data.

Our conclusions are consistent with those of a previous study (26), that evaluated patients from the SEER database who were diagnosed between 2004 and 2012. However, unlike our study, this earlier study did not incorporate metastatic sites which are considered as a key risk factor for survival, into the analysis, since information on collaborative staging in the SEER database was available only from 2010.

The better survival in the gastrectomy group can be partially attributed to the decrease in tumor-related gastrointestinal bleeding, perforation or obstruction. Nevertheless, not all patients with stage IV gastric cancer benefit from palliative gastrectomy. Older patients with higher grade non-adenocarcinomas or with lung metastasis benefit less from gastrectomy. Therefore, for such patients, surgical complications should be a major consideration, despite the recent advances in surgical techniques such as minimally invasive surgery and postoperative nutrition management (27). Higher grade tumors usually cause rapid progression of the disease, and surgical resection of these tumors could trigger accelerated metastasis. Our analysis shows that chemotherapy with palliative gastrectomy provides additional benefits and should be recommended for the performance status fitted patient. But, the database did not provided the information on sequence of chemotherapy and surgery. In clinical practice, except for emergency of surgery, preoperational chemotherapy is considered as optimal choice for some cases (28). In line with previous reports (29,30), even after PSM, our analysis found that lung metastasis was an independent risk factor for survival and therefore should be considered while making a decision regarding palliative surgery.

There were also some limitations for this study. First, due to data availability, some important parameters which may have important impact on survival of gastric cancer patients, for example, patients’ performance status, comorbidities, complications, et al. cannot be obtained in SEER database, so, may be, there were some imbalance between gastrectomy group and no gastrectomy group. Especially, as we know, peritoneal metastasis is common in gastric cancer, and recent evidences showed that patients with peritoneal metastasis may benefit from neoadjuvant intraperitoneal and systemic chemotherapy (NIPS) followed by surgery (28). Unfortunately, due to defects of SEER database, the proportions of peritoneal metastasis in the two groups were unknown. Second, the PSM method used in our study may have some bias. The results of current study should be validated in further prospectively designed trials with more detailed information.

Conclusions

Palliative gastrectomy provides survival benefits to stage IV gastric cancer patients. However, age, tumor type, tumor grade, and metastasis status should be considered before opting for this procedure. In addition, chemotherapy should be recommended for patients who undergo palliative surgery.

Acknowledgments

Funding: Chang-Hao Wu gratefully acknowledges support from Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC) (BB/P004695/1) and National Institute of Aging (NIA, 1R01AG049321-01A1). This study was funded by grants from Anhui Provincial Key Research and Development Program [1804b06020351] and National Natural Science Foundation of China [81572430, 81872047].

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/jgo.2020.01.07). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin 2015;65:87-108. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Arsoniadis EG, Marmor S, Diep GK, et al. Survival Rates for Patients with Resected Gastric Adenocarcinoma Finally have Increased in the United States. Ann Surg Oncol 2017;24:3361-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fujitani K, Yang HK, Mizusawa J, et al. Gastrectomy plus chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for advanced gastric cancer with a single non-curable factor (REGATTA): a phase 3, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 2016;17:309-18. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sun J, Song Y, Wang Z, et al. Clinical significance of palliative gastrectomy on the survival of patients with incurable advanced gastric cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cancer 2013;13:577. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yazıcı O, Ozdemir N, Duran AO, et al. The effect of the gastrectomy on survival in patients with metastatic gastric cancer: a study of ASMO. Future Oncol 2016;12:343-54. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tokunaga M, Terashima M, Tanizawa Y, et al. Survival benefit of palliative gastrectomy in gastric cancer patients with peritoneal metastasis. World J Surg 2012;36:2637-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chang YR, Han DS, Kong SH, et al. The value of palliative gastrectomy in gastric cancer with distant metastasis. Ann Surg Oncol 2012;19:1231-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kunisaki C, Makino H, Takagawa R, et al. Impact of palliative gastrectomy in patients with incurable advanced gastric cancer. Anticancer Res 2008;28:1309-15. [PubMed]

- Hsu JT, Liao JA, Chuang HC, et al. Palliative gastrectomy is beneficial in selected cases of metastatic gastric cancer. BMC Palliat Care 2017;16:19. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tokunaga M, Makuuchi R, Miki Y, et al. Surgical and Survival Outcome Following Truly Palliative Gastrectomy in Patients with Incurable Gastric Cancer. World J Surg 2016;40:1172-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chiu CF, Yang HR, Yang MD, et al. Palliative Gastrectomy Prolongs Survival of Metastatic Gastric Cancer Patients with Normal Preoperative CEA or CA19-9 Values: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Gastroenterol Res Pract 2016;2016:6846027.

- Khozin S, Blumenthal GM, Pazdur R. Real-world Data for Clinical Evidence Generation in Oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst 2017. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Camp RL, Dolled-Filhart M, Rimm DL. X-tile: a new bio-informatics tool for biomarker assessment and outcome-based cut-point optimization. Clin Cancer Res 2004;10:7252-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- D'Agostino RB Jr. Propensity score methods for bias reduction in the comparison of a treatment to a non-randomized control group. Stat Med 1998;17:2265-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Newgard CD, Hedges JR, Arthur M, et al. Advanced statistics: the propensity score--a method for estimating treatment effect in observational research. Acad Emerg Med 2004;11:953-61. [PubMed]

- Harris E, Barry M, Kell MR. Meta-analysis to determine if surgical resection of the primary tumour in the setting of stage IV breast cancer impacts on survival. Ann Surg Oncol 2013;20:2828-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lane WO, Thomas SM, Blitzblau RC, et al. Surgical Resection of the Primary Tumor in Women With De Novo Stage IV Breast Cancer: Contemporary Practice Patterns and Survival Analysis. Ann Surg 2019;269:537-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ahmed S, Fields A, Pahwa P, et al. Surgical Resection of Primary Tumor in Asymptomatic or Minimally Symptomatic Patients With Stage IV Colorectal Cancer: A Canadian Province Experience. Clin Colorectal Cancer 2015;14:e41-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ahmed S, Leis A, Fields A, et al. Survival impact of surgical resection of primary tumor in patients with stage IV colorectal cancer: results from a large population-based cohort study. Cancer 2014;120:683-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Danna EA, Sinha P, Gilbert M, et al. Surgical removal of primary tumor reverses tumor-induced immunosuppression despite the presence of metastatic disease. Cancer Res 2004;64:2205-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Flanigan RC, Salmon SE, Blumenstein BA, et al. Nephrectomy followed by interferon alfa-2b compared with interferon alfa-2b alone for metastatic renal-cell cancer. N Engl J Med 2001;345:1655-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mickisch GH, Garin A, van Poppel H, et al. Radical nephrectomy plus interferon-alfa-based immunotherapy compared with interferon alfa alone in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma: a randomised trial. Lancet 2001;358:966-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Graham J, Heng DY. Real-world evidence in metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Tumori 2018;104:76-82. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Amini N, Spolverato G, Kim Y, et al. Clinicopathological features and prognosis of gastric cardia adenocarcinoma: a multi-institutional US study. J Surg Oncol 2015;111:285-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang X, Liu F, Li Y, et al. Comparison on Clinicopathological Features, Treatments and Prognosis between Proximal Gastric Cancer and Distal Gastric Cancer: A National Cancer Data Base Analysis. J Cancer 2019;10:3145-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- He X, Lai S, Su T, et al. Survival benefits of gastrectomy in gastric cancer patients with stage IV: a population-based study. Oncotarget 2017;8:106577-86. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shiozaki H, Shimodaira Y, Elimova E, et al. Evolution of gastric surgery techniques and outcomes. Chin J Cancer 2016;35:69. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gong Y, Wang P, Zhu Z, et al. Benefits of Surgery After Neoadjuvant Intraperitoneal and Systemic Chemotherapy for Gastric Cancer Patients With Peritoneal Metastasis: A Meta-Analysis. J Surg Res 2020;245:234-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kong JH, Lee J, Yi CA, et al. Lung metastases in metastatic gastric cancer: pattern of lung metastases and clinical outcome. Gastric Cancer 2012;15:292-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Qiu MZ, Shi SM, Chen ZH, et al. Frequency and clinicopathological features of metastasis to liver, lung, bone, and brain from gastric cancer: A SEER-based study. Cancer Med 2018;7:3662-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]