Sister Mary Jospeh’s nodule as initial presentation of carcinoma caecum-case report and literature review

Introduction

Cutaneous metastases localized to the umbilicus are known by the eponym Sister Mary Joseph’s nodules (SMJN). Cutaneous metastases occur in less than 10% of all malignancies and among the cutaneous metastases, umbilicus is the site of metastases in less than 10% (1). Among all reported cases of SMJN, 35-65% metastasizes from the gastrointestinal tract (GIT), 12-35% from the genitourinary tract (GUT), 15-30% from unknown sites and 3-6% from other sites such as lung and breast (2). These nodules are seen predominantly in women.

Case report

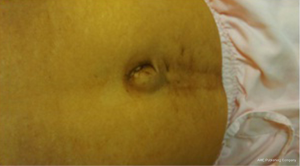

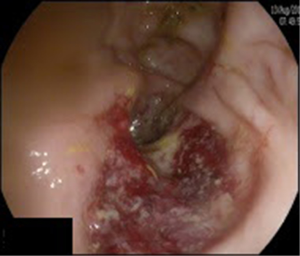

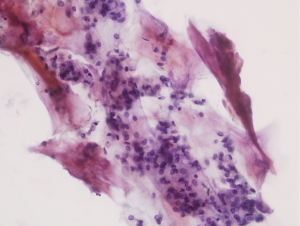

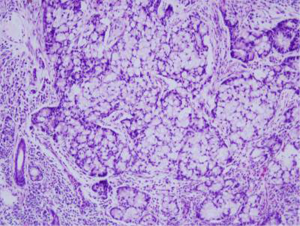

A 45-year-old lady with no family history of gastrointestinal tumors presented with complaints of abdominal pain which was worsening over the last 1 week and pain was associated with occasional vomiting. She had no history of bleeding per rectum or melaena. She is a known hypertensive, hypothyroid and is on medications for the same. Physical examination revealed a 1.5 cm cystic to solid nodule in the umbilicus and it was not trans-illuminant (Figure 1). She had mild to moderate ascites, no abdominal guarding, and no hepatosplenomegaly. Digital rectal examination showed internal haemorrhoids. She had no palpable lymphadenopathy. Rest of the physical examination was unremarkable. CT scan of the thorax/abdomen showed no lung lesions, no pleural effusion, mild to moderate ascites, no intra-abdominal lymphadenopathy, no peritoneal deposits and a 2 cm umbilical nodule. TVUS showed bulky uterus with a mild inhomogeneous right ovary. In view of umbilical nodule and ascites on the imaging, tumor markers were done in an effort to exclude any malignancy. Her tumor markers were found to be markedly elevated. (CA19.9, 573; CEA, 161; CA125, 700). Fine needle aspiration cytology from the umbilical nodule showed cells suggestive of metastatic adenocarcinoma (Figure 2). Upper GI endoscopy was normal and Colonoscopy showed a mass in the caecum (Figure 3). Biopsy from the caecum was reported as moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma (Figure 4). Her case was discussed in the multidisciplinary tumor board and in view of metastatic disease in the umbilicus she was planned for chemotherapy. She was started with XELOX chemotherapy regimen and she was found to have good biochemical response (CA19.9, 241; CEA, 44.5; CA125, 59.3) and radiologically partial response after three cycles. Post six cycles chemotherapy she was found to have disease progression and was started on next line of chemotherapy with FOLFIRI.

Discussion

Umbilical metastasis from intra-abdominal primary tumors was first reported by Walsh et al. in 1846. In the 1920s these metastases were described as “trouser button navel” by William James Mayo. The association between the umbilical nodules and the advanced intra-abdominal tumors was identified by Sister Mary Joseph from Mayo clinic on whose honor these nodules are named as SMJN (3).

SMJN is one of the unfavorable prognostic sign and it is associated with inoperable tumor and overall survival of 2-11 months in untreated patients (3). The most common intra abdominal tumors associated with these nodules are from the stomach and ovary. Within the large bowel, the caecum is the least frequent primary site and to our best knowledge less than 20 cases have been reported in literature.

Galvañ et al. (4) in his review of 407 patients with umbilical metastases from 1966 to 1997 and found that 14.6% of all cases were originated from colorectal cancers. While reviewing literature in the context of right side colon tumors contributing to SMJN, there are only case reports. According to Gabriele (5) SMJN originated from caecum cancer is very rare and only four cases have been reported in literature. Dodiuk-Gad et al. (6), Wu et al. (7) and Moll (8) have reported one case each of carcinoma caecum with SMNJ.

The mechanism by which the tumor cells reach the umbilicus is not clearly documented. However several hypotheses that have been proposed are summarized below (5,9,10).

- Lymphatic spread via the retrograde subserosal lymphatics from axillary, inguinal and para aortic nodes (common for gynaecological, renal tumors);

- Arterial spread through the anastomosis between the inferior epigastric, lateral thoracic and the internal mammary arteries (common for gynaecological tumors);

- Venous spread through (common for gynecological tumors, renal tumors);

- The anastomotic braches from the axillary veins, internal mammary veins and the femoral veins;

- The portal system via the small umbilical veins;

- Direct extension through the peritoneum (common for gastrointestinal tumors);

- Through the urachus, remains of omphalomesenteric duct and falciform ligament (common for spread of genitourinary tumors).

Majority of the patients present with complaints of abdominal pain, distension, weight loss, vomiting, ascites which are all symptoms suggestive of an intra-abdominal cancer. These nodules are easily picked up on physical examination but sometimes in obese people it might be easily overlooked. These nodules could easily be demonstrated in the ultrasound or contrast enhanced CT. The diagnostic evaluation of umbilical nodule is ideally to perform a FNAC (11) after excluding hernia. There have been case reports where these nodules have been found as early as 8 months ahead of detection of early caecal adenocarcinoma (12).

The differential diagnosis includes the benign lesions (such as papillomas, myxomas, endometriosis, foreign body granulomas, and umbilical hernia), malignant lesions (such as melanomas, sarcomas, basal cell carcinoma) and metastatic deposits.

Even though the presence of SMJN indicates disseminated malignant disease, the prognosis of the patients depends on the treatment offered, type of tumor and the primary tumor site.

The prognosis is also more favorable when the SMJN is detected before the primary tumor rather than after the treatment for the primary tumor (9.7 vs. 7.6 months) (6).

There is no management guidelines published so far for the management of colon carcinoma patients with SMNJ. The role of surgery in patients with SMJN is debatable. Most researchers have often suggested having either palliative or conservative management. Recent articles have shown that aggressive multimodality treatment approach which includes surgery and chemotherapy has shown to improve the survival than those who have been treated with a single modality (13,14) (survival: surgery + chemo—17.6 months; chemotherapy alone—10.3 months; surgery alone—7.4 months; best supportive care—2.3 months). Since there is tremendous improvement in the management of colorectal tumors in the last two decades with introduction of newer chemotherapeutic drugs, targeted agents such as bevacizumab, aflibercept the chances of increasing the tumor response has increased considerably. These agents should be used in combination to get good results and surgery should be limited to the patient population who present with bleeding, obstruction, perforation or in patients with solitary umbilical metastasis.

Conclusions

All umbilical nodules should be biopsied as their metastases are associated with poor prognosis. The ease of identification of the nodule underlines the importance of good clinical examination. Identification of these nodules needs high awareness, increased levels of clinical suspicion and would lead to appropriate prognostication of the patients. Combined modality treatment is the way forward in these groups of patients.

Acknowledgements

Consent: Informed consent has been obtained from the patient for publishing the case and a copy of the same is available with the author.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflict of interests.

References

- Lookingbill DP, Spangler N, Sexton FM. Skin involvement as the presenting sign of internal carcinoma. A retrospective study of 7316 cancer patients. J Am Acad Dermatol 1990;22:19-26. [PubMed]

- Falchi M, Cecchini G, Derchi LE. Umbilical metastasis as first sign of cecal carcinoma in a cirrhotic patient (Sister Mary Joseph nodule). Report of a case. Radiol Med 1999;98:94-6. [PubMed]

- Bailey H, editor. Demonstrations of Physical Signs in Clinical Surgery. 11th edition revised. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins co., Baltimore Maryland, 1949.

- Galvañ VG. Sister Mary Joseph’s nodule. Ann Intern Med 1998;128:410. [PubMed]

- Gabriele R, Conte M, Egidi F, et al. Umbilical metastases: current viewpoint. World J Surg Oncol 2005;3:13. [PubMed]

- Dodiuk-Gad R, Ziv M, Loven D, et al. Sister Mary Joseph’s nodule as a presenting sign of internal malignancy. Skinmed 2006;5:256-8. [PubMed]

- Wu YY, Xing CG, Jiang JX, et al. Carcinoma of the right side colon accompanied by Sister Mary Joseph's nodule and inguinal nodal metastases: a case report and literature review. Chin J Cancer 2010;29:239-41. [PubMed]

- Moll S. Images in clinical medicine. Sister Joseph’s node in carcinoma of the cecum. N Engl J Med 1996;335:1568. [PubMed]

- Ching AS, Lai CW. Sonography of umbilical metastasis (Sister Mary Joseph’s nodule): from embryology to imaging. Abdom Imaging 2002;27:746-9. [PubMed]

- Jager RM, Max MH. Umbilical metastasis as the presenting symptom of cecal carcinoma. J Surg Oncol 1979;12:41-5. [PubMed]

- Handa U, Garg S, Mohan H. Fine-needle aspiration cytology of Sister Mary Joseph's (paraumbilical) nodules. Diagn Cytopathol 2008;36:348-50. [PubMed]

- Salemis NS. Umbilical metastasis or Sister Mary Joseph's nodule as a very early sign of an occult cecal adenocarcinoma. J Gastrointest Cancer 2007;38:131-4. [PubMed]

- Majmudar B, Wiskind AK, Croft BN, et al. The Sister (Mary) Joseph nodule: its significance in gynecology. Gynecol Oncol 1991;40:152-9. [PubMed]

- Palaniappan M, Jose WM, Mehta A, et al. Umbilical metastasis: a case series of four Sister Joseph nodules from four different visceral malignancies. Curr Oncol 2010;17:78-81. [PubMed]