Quality of life as a fundamental outcome after curative intent gastrectomy for adenocarcinoma: lessons learned from patients

Introduction

Gastric cancer has an important epidemiologic impact, and the main curative therapeutic modality for gastric cancer is surgical resection (1-3). An interdisciplinary and multimodal approach can lead to improved outcomes and gains in survival (4-7). However, even curative intent therapy may result in negative effects on the quality of life (QoL) of these patients; thus, balancing standardized treatment reported in the literature and the treatment response to achieve full patient satisfaction is difficult (8,9).

The concept of QoL has been widely discussed in the literature (8). The World Health Organization (WHO) defines QoL as “an individual’s perception of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems (including spiritual) in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards and concerns” (9-11). The concept most frequently used in health-related studies is health-related QoL, which considers the impact of a disease and its treatment on an individual and is centered on a subjective evaluation reported by the patient regarding the impact of his or her health status on his or her ability to live fully (11-13).

Health-related QoL assessments are published in multiple languages and serve as internationally validated, reproducible and comparable scientific instruments that consider multidimensional features and evaluate an individual’s perception of his or her QoL. These instruments can be generic when they are applied nonspecifically for different diseases to provide a broad view, such as the Short Form 36 Health Survey version 2 (SF-36v2) questionnaire, or they can be specific when applied to identify characteristics related to a particular disease by emphasizing the symptoms or limitations; for instance, for gastric cancer, the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Gastric (FACT-Ga) questionnaire is available (10-27).

This study aims to evaluate the QoL outcomes of gastric adenocarcinoma patients undergoing curative intent surgical treatment and to identify the associations of FACT-Ga and SF-36v2 scores with clinical, demographic, and epidemiologic aspects, histologic variables, and the treatment modality used. The contribution of this study is the quantification of previously abstract and immeasurable aspects through the use of scientifically validated statistical tools (the questionnaires), with full evaluation of therapeutic responses and the effects reported by the patients themselves in the various dimensions of their lives related to their illnesses.

Methods

Participants

This cross-sectional study was conducted over a period of 12 months and was approved by two institutional review boards (Base Hospital Institute, Brasília and Amaral Carvalho Cancer Hospital, São Paulo) through inclusion in the Plataforma Brasil under CAAE number 55759516.8.1001.5553 and approval in opinions 1,576,222 and 1,863,271. All patients signed written informed consent prior to study enrollment. This study was performed in accordance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki [1964] and its later amendments.

Subjects were selected randomly and sequentially at a variable postoperative interval. The subjects were gastric adenocarcinoma patients who were previously treated with curative intent surgeries (performed by the care team) at three different centers in Brazil: Brasília (Federal District), Jaú (São Paulo) and Macapá (Amapá). The purpose of this study was discussed with all subjects, and they provided written informed consent to participate. Medical records were searched, and relevant data were collected. QoL questionnaires were administered by trained doctors (some of the authors), and the scores were compared to the other variables cited.

QoL assessment

The Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (MOS-SF-36) consists of 36 items encompassing 8 domains: physical functioning, role-physical, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, role-emotional and mental health. For each question, a score value for each of the 8 domains is assigned ranging from 0= worst to 100= best (11,16,20,21,23). The SF-36 is a short-form, multipurpose generic instrument and has been widely used in a variety of specific and nonspecific populations. The SF-36 has been demonstrated to be sound psychometrically, and it is frequently used to establish convergent validity (26).

The FACT-Ga is a specific internationally validated instrument for assessing QoL in patients with gastric cancer consisting of 27 items and is divided into scales of physical well-being (PWB), functional well-being (FWB), social/family well-being (SWB), emotional well-being (EWB), and a gastric cancer subscale (GaCS). The instrument contains questions about specific symptoms regarding gastric cancer that allow a trial outcome index (TOI = PWB + FWB + GaCS), a FACT-General (FACT-G) total score (PWB + SWB + EWB + FWB) or a FACT-Ga total score (PWB + SWB + EWB + FWB + GaCS) to be determined. The sum of the scores for each question is associated with higher/better polarity, with the highest score corresponding to a better QoL, and the scale is accepted as an indicator of QoL when more than 80% of the items are answered (26,27). The FACT-Ga is a part of the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy (FACIT) measurement system. It is intended for use in patients at all disease stages throughout the treatment course and has particular applicability for determining treatment effects on QoL (26).

Both the SF-36v2 and FACT-Ga questionnaires have been utilized in Portuguese and validated for use in the Brazilian population.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with the program R version 3.3.2 (28). A descriptive data analysis was initially performed, and the results are reported as the average, median, minimum and maximum values, standard deviation, and absolute and relative frequencies (percentages).

The inferential analyses used to confirm or refute evidence were as follows: the Mann-Whitney test (29) was used to compare differences in genders and neoadjuvant and adjuvant treatments with SF-36v2 and FACT-Ga scores in the various domains; the Kruskal-Wallis test (30) was used to compare differences in genders, education level, income level, tumor site, the type of surgery performed, histopathology (Lauren classification), and neoadjuvant and adjuvant treatments with SF-36v2 and FACT-Ga scores; and Spearman’s correlation coefficient (29) was used to compare differences in age, treatment time, tumor staging, lymph node stage, metastasis, tumor grade and the number of resected lymph nodes with SF-36v2 and FACT-Ga scores. Multiple regression was used to correlate the QoL questionnaire scores with the following variables: education level, gender, income level, treatment time, tumor location, type of gastrectomy, neoadjuvant treatment, adjuvant treatment, N (TNM), T (TNM), Helicobacter pylori status, Lauren’s histology, and number of lymph nodes removed during lymphadenectomy. For all comparisons, the alpha level of significance was 5%.

Results

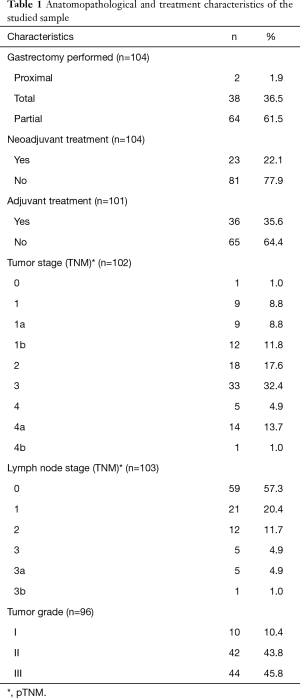

The selected sample included 104 patients with gastric adenocarcinoma undergoing surgical treatment with curative intent, of whom 23 (22.1%) were from center A (Amapá), 43 (41.3%) were from center B (Brasília), and 38 (36.5%) were from center J (Jaú). Patients were consulted and interviewed regarding QoL during the postoperative periods; individuals were identified at different treatment times ranging from 0.3 months (8 days) to 125.9 months (average 24.2, median 17.8, standard deviation 23.1 months) as measured from the day of surgery to the date of completion of the questionnaires. Fifty participants (48.1%) were women, and 54 (51.9%) were men. The mean age was 59.8 years, with a range of 29.4 to 93.6 years. Approximately 54.9% of the patients were smokers, and Helicobacter pylori infection was present in 40.6% of the patients. Lauren’s intestinal histology was the most frequent type of pathology and was observed in 62 patients (61.4%). An average of 22.2 (2 to 55) lymph nodes were removed during lymphadenectomy. The other anatomopathological and treatment characteristics of the studied sample are shown in Table 1.

Full table

According to the GaCS of the FACT-Ga questionnaire, which records responses as “Not at all”, “A little bit”, “Somewhat”, “Quite a bit” or “Very much” for the questions about specific symptoms regarding gastric cancer, answers of “Somewhat”, “Quite a bit” or “Very much” were recorded for the following percentages of patients: losing weight 28.1%, loss of appetite 42.6%, bothered by reflux or heartburn 26%, able to eat the foods that I like 80.1%, discomfort or pain when eating 28.1%, feeling of fullness or heaviness in the stomach area 35.4%, swelling or cramps in the stomach area 20.1%, trouble swallowing food 11.4%, bothered by a change in eating habits 31.9%, able to enjoy meals with family or friends 81.3%, avoiding going out to eat because of illness 38.5%, concerned by stomach problems 31%, discomfort or pain in the stomach area 25%, bothered by flatulence 46.8%, diarrhea 33.3%, feeling tired 32.2%, feeling weak all over 28.1%, have difficulty planning for the future because of illness 20.8%, and digestive problems interfere with usual activities 20.8%.

In the multiple regression analysis, the correlations of QoL questionnaire scores with the following variables were analyzed: education level, gender, income level, postoperative time, tumor site, type of gastrectomy, neoadjuvant treatment, adjuvant treatment, N (TNM), T (TNM), Helicobacter pylori status, Lauren’s histology, and number of lymph nodes removed during lymphadenectomy. We found statistically significant correlations between tumor site and EWB (cardia had better scores, P=0.038), between Helicobacter pylori status and PWB (positive status had better scores, P=0.026), between sex and EWB (women had better scores, P=0.008), and between Lauren’s histology and physical functioning (diffuse type had better scores, P=0.009), between Lauren’s histology and the physical domain of the SF-36v2 (P=0.027), between the SF-36v2 mental health domain and N (the lower the stage was, the better the score, P=0.006) and between the SF-36v2 mental health domain and the number of lymph nodes removed during lymphadenectomy (the higher the number was, the better the score, P=0.029). The other variables were not correlated with the questionnaire scores.

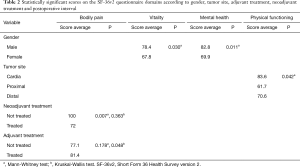

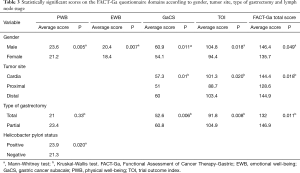

Women had worse scores for PWB, EWB, the GaCS, and the TOI and poorer FACT-Ga total scores, vitality and mental health than men (Tables 2 and 3). Patients who underwent partial gastrectomy had better scores in the domains of PWB, the GaCS, the TOI and FACT-Ga total score than those who underwent total gastrectomy (Tables 2 and 3). Helicobacter pylori positivity was associated with better scores for PWB (Tables 3).

Full table

Full table

Only the GaCS, TOI, FACT-Ga total score and physical functioning (Tables 2 and 3) were related to the tumor site. Patients with proximal tumors had worse GaCS, TOI and FACT-Ga total scores than patients with distal tumors. Patients with proximal tumors had worse FACT-Ga total scores and physical functioning scores than patients with tumors located in the cardia. Patients with distal tumors had better scores in the domains of the GaCS, TOI, and FACT-Ga total score than patients with proximal tumors, while patients with tumors located in the cardia had better scores in the physical functioning domain than patients with proximal tumors (Table 2).

Patients who received neoadjuvant treatment had worse scores in the bodily pain domain than patients who did not receive this treatment (no significance with the Kruskal-Wallis test and P=0.007 with the Mann-Whitney test). For the other domains of both questionnaires, no relationship between the use of neoadjuvant treatment and QoL measures could be shown (Table 3). Patients who did not receive any adjuvant treatment had worse scores in the bodily pain domain than patients who received some type of adjuvant treatment (P=0.048 with the Kruskal-Wallis test and no significance with the Mann-Whitney test).

Spearman’s correlation coefficient showed statistically significant associations of postoperative time (months) and lymph node stage with the FACT-Ga and SF-36v2 domains. A longer time after treatment corresponded to a better score for the SF-36 role-physical domain (s=0.223, P=0.023). A higher lymph node stage corresponded to a lower GaCS score (P=0.037, s=−0.206), TOI (P=0.028, s=−0.216), FACT-Ga total score (P=0.043, s=0.20) and SF-36v2 vitality domain score (P=0.029, s=−0.215).

The other non-cited variables (histological Lauren types, age, income level and education level) were not statistically significantly (according to the Kruskal-Wallis or Mann-Whitney test) associated with QoL outcome measures (SF-36v2 or FACT-Ga).

Discussion

Gastric cancer is an important disease with a variable social impact, and its complex treatment requires cooperation among physicians with different knowledge and health care specialties (30-34). However, even curative intent therapy may result in negative effects on health-related QoL, complicating the balance between standardized treatment and complete and improved responses (including patients’ perceptions and expectations about their illness) (4,8,9,30).

Currently, the study of QoL involves several validated and standardized statistical inferential tools that have allowed improvements in research in this area. These tools preserve the subjectivity and multidimensional characteristics of QoL, quantify a patient’s emotional, psychological, physical, cognitive, social, environmental and family aspects, and assess the influence of cancer-specific signs and symptoms (10,12,35-37). Developments in this field have led to the possibility of using a patient’s self-reported information in research, treatment planning and implementation of preventive strategies, as well as opportunities to teach multidisciplinary assistant teams to consider the undeniable protagonism and autonomy of the patient.

The retrospective design of this study did not allow comparisons with preoperative QoL scores; however, the application of QoL research tools during the preoperative period would represent the condition of the disease at that time and not the impact of the treatment. We also note that the questionnaires can measure changes in scores over time, showing improvement or worsening in relation to the previous condition through specific questions already present in some of these instruments.

Our data suggest that the significant associations between the QoL outcomes and trinomial factors (patient + disease + treatment) are more related to the type of treatment rather than epidemiological, demographic or some anatomopathological characteristics. Regarding age, income level and education level, no significant differences were identified; thus, if these variables do not interact with other technical aspects and the oncological safety of the treatment, they should not be included as relevant data during decision-making or when selecting the final therapy, although education level has been reported to be a factor that influences QoL by some authors (37-39). The apparently complex and statistically significant correlations found in this study suggested that the status of Helicobacter pylori and gastric cancer should be analyzed with appropriately designed studies to verify our results.

However, within the demographic characteristics, the present analysis shows a correlation between gender and EWB and that women had lower scores for PWB, EWB, the GaCS, and the TOI and poorer FACT-Ga total scores, vitality and mental health than men (according to Mann-Whitney and Kruskal-Wallis tests). Therefore, the interdisciplinary relationships associated with surgical treatment should be strengthened with the early introduction of health care interventions, including spiritual support for all patients and possibly more careful attention to women in relation to their specific characteristics. Additional studies are necessary to elucidate this assumption or to determine appropriate conclusions.

By analyzing the inherent characteristics of the tumors, we showed correlations between Lauren’s histology and PWB, physical functioning and the SF-36v2 role-physical domain in the multiple regression analysis; intriguingly, the diffuse, clinically more aggressive type was associated with better scores. However, Lauren’s histology does not affect QoL (according to Mann-Whitney and Kruskal-Wallis tests), which suggests that this characteristic may not interfere in therapeutic definitions aimed at QoL. Therefore, histology alone may be insufficient for defining treatment strategies and prognosis; thus, further research in the field of classification and identification of tumor cell subtypes is necessary (1-3,9,30).

By attempting to correlate initial stages with improved QoL, we showed that a higher lymph node stage (more advanced disease) was associated with worse outcomes for some scores and the higher the number of lymph nodes removed during lymphadenectomy, the better some scores were. This finding suggests, in the authors’ opinion, that specialized treatment for gastric cancer with well-executed lymphadenectomy and resection decreases the morbidity and mortality related to the procedure and the disease. Teams with appropriate experience can perform more extensive lymphadenectomy and resect more lymph nodes, allowing improved staging that consequently improves the therapeutic strategy and survival (38-43). In addition, the idea of a negative impact associated with the extent of lymphadenectomy on QoL was apparently refuted, reinforcing the oncological indications for this procedure.

The tumor location in the stomach was also found to significantly influence QoL. Distal tumors and partial gastrectomy were associated with better QoL scores than proximal tumors and total gastrectomy. These results are compatible with other literature reports because the tumor location in the organ defines the treatment in terms of the extent of gastric resection. Proximal tumors require total gastrectomy with proximal surgical margins of 5 cm, whereas distal tumors can be treated with subtotal or partial gastrectomy, which are better-tolerated procedures with less morbidity than total gastrectomy (9,30,32-34,38,44-52).

Some symptoms that influence QoL can be attributed to changes in nutritional status and the remaining gastric reservoir (51), but more studies should be performed to elucidate this point (in our study, digestive problems interfered with usual activities in 20.8% of patients). Interestingly, even without definitive data for further discussion, patients with tumors located in the cardia had better scores in the physical functioning domain (SF-36) than those with tumors located in proximal sites. Perhaps the clinical characteristics and symptoms of tumors located in the cardia in combination with the present findings can allow earlier diagnosis at an earlier stage when fewer clinical repercussions exist. Furthermore, in our study, as reported by other authors, partial gastrectomy is significantly superior when QoL outcomes are studied and should be preferred whenever appropriate (9,10,30,32-34,38,44-53).

A clear relationship also exists between improvement in QoL scores and the postoperative interval (53,54). The surgical procedure itself is a factor that worsens QoL, which was also found to be significant in our study. The literature reports that improvement in QoL starts at 3 months postoperatively, is substantial after 6 months, and may completely recover according to some authors, with resolution of symptoms associated with surgical sequelae between 12 and 24 months (44,45,54-59). In patients with cardia tumors, esophagectomy scores seem to match total gastrectomy scores from the sixth month (50). This temporal relationship of QoL should be used for planning preventive measures for symptom control with intensification of treatment and for optimized targeting of resources during the most critical period.

In our study, patients who did not receive adjuvant treatment had worse scores in the SF-36v2 bodily pain domain than patients who received some adjuvant therapy. Patients who underwent neoadjuvant treatment had worse scores in the bodily pain domain than patients who did not receive such treatment. These data suggest a complex relationship between treatment modalities and interference with QoL, and the benefits and safety of treatment modalities should always be analyzed considering the best scientific evidence available. In oncology, no treatment is innocuous, even if it is efficient and effective, and treatment selection must be absolutely judicious such that the true benefit is unambiguous (53-66).

The information reported on QoL outcomes can be used to configure a paradigm-shifting tool for the treatment and rescue of patient protagonism with rational and preventive interventions. Different influences of therapeutic modalities and their interrelationships with QoL outcomes should be meticulously investigated. Additionally, construction of interdisciplinary lines of care should be a priority to improve outcomes (37). Studies of economic and social impacts should be encouraged to subsidize management and decision makers and to confirm our perception that only a combination of the best specialized knowledge can mitigate suffering related to gastric cancer.

In conclusion, associations of clinical and pathological factors, the type of treatment, postoperative time, and sociodemographic factors with the FACT-Ga and SF-36v2 scores for QoL outcomes reported by adenocarcinoma patients undergoing curative intent surgical treatment were identified. Data from QoL outcome research can and should be used to inform decisions regarding therapeutic planning, bringing patients’ choices and perceptions to the forefront to teach assisting teams about the irrefutable relevance of patient protagonism. Future trials with adequate health-related QoL questionnaires in multiple languages and using internationally-validated instruments are needed to appropriately answer further questions.

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The present study protocol was approved by two institutional review boards through inclusion in the Plataforma Brasil under CAAE number 55759516.8.1001.5553 and approval in opinions 1,576,222 and 1,863,271. All patients signed written informed consent prior to study enrollment. This study was performed in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki [1964] and later versions. The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

References

- INCA. Instituto nacional de câncer josé alencar gomes da silva. Rio de Janeiro: INCA, 2018.

- PDQ® Adult Treatment Editorial Board. PDQ gastric cancer treatment. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute, 2018.

- Campello JCL, Lima LC. Perfil clínico epidemiológico do câncer gástrico precoce em um hospital de referência em Terezina, Piauí. Rev Bras Cancerol 2012;58:15-20.

- Newton AD, Datta J, Loaiza-Bonilla A, et al. Neoadjuvant therapy for gastric cancer: Current evidence and future directions. J Gastrointest Oncol 2015;6:534-43. [PubMed]

- Schuhmacher C, Reim D, Novotny A. Neoadjuvant treatment for gastric cancer. J Gastric Cancer 2013;13:73-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ahn HS, Jeong SH, Son YG, et al. Effect of neoadjuvant chemotherapy on postoperative morbidity and mortality in patients with locally advanced gastric cancer. Br J Surg 2014;101:1560-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Li W, Qin J, Sun YH, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy for advanced gastric cancer: A meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol 2010;16:5621-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rausei S, Mangano A, Galli F, et al. Quality of life after gastrectomy for cancer evaluated via the EORTC QLQ-C30 and QLQ-STO22 questionnaires: Surgical considerations from the analysis of 103 patients. Int J Surg 2013;11:S104-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Orditura M, Galizia G, Sforza V, et al. Treatment of gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2014;20:1635-49. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kaptein AA, Morita S, Sakamoto J. Quality of life in gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2005;11:3189-96. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- The WHOQOL Group. The world health organization quality of life assessment (WHOQOL): Development and general psychometric properties. Soc Sci Med 1998;46:1569-85. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Seidl EMF. Zannon CMLdC. Qualidade de vida e saúde: Aspectos conceituais e metodológicos. Cad Saúde Pública 2004;20:580-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ciconelli RM, Ferraz MB, Santos W, et al. Tradução para a língua portuguesa e validação do questionário genérico de avaliação de qualidade de vida SF-36 (Brasil SF-36). Rev Bras Reumatol 1999;39:143-50.

- Scoggins JF, Patrick DL. The use of patient-reported outcomes instruments in registered clinical trials: Evidence from clinical trials.gov. Contemp Clin Trials 2009;30:289-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Heydarnejad MS, Hassanpour DA, Solati DK. Factors affecting quality of life in cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. Afr Health Sci 2011;11:266-70. [PubMed]

- Laguardia J, Campos MR, Travassos CM, et al. Psychometric evaluation of the SF-36 (v.2) questionnaire in a probability sample of Brazilian households: Results of the survey pesquisa dimensoes sociais das desigualdades (PDSD), Brazil, 2008. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2011;9:61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jay CL, Butt Z, Ladner DP, et al. A review of quality of life instruments used in liver transplantation. J Hepatol 2009;51:949-59. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Aguiar CCT, Vieira APGF, Carvalho AF, et al. Instrumentos de avaliação de qualidade de vida relacionada à saúde no diabetes melito. Arq Bras Endocrinol Metab 2008;52:931-9. [Crossref]

- Mucci S. Adaptação cultural do chronic liver disease questionnaire (CLDQ) para população brasileira. Cad Saúde Pública 2010;26:199-205. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mucci S, de Albuquerque Citero V, Gonzalez AM, et al. Validation of the Brazilian version of chronic liver disease questionnaire. Qual Life Res 2013;22:167-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gandek B, Sinclair SJ, Kosinski M, et al. Psychometric evaluation of the SF-36 health survey in medicare managed care. Health Care Financ Rev 2004;25:5-25. [PubMed]

- Skevington SM, Lotfy M, O'Connell KA. The world health organization's WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment: Psychometric properties and results of the international field trial. A report from the WHOQOL group. Qual Life Res 2004;13:299-310. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Campolina AG, Ciconelli RM. O. SF-36 e o desenvolvimento de novas medidas de avaliação de qualidade de vida. Acta Reumatol Port 2008;33:127-33. [PubMed]

- Blazeby JM, Conroy T, Bottomley A, et al. Clinical and psychometric validation of a questionnaire module, the EORTC QLQ-STO 22, to assess quality of life in patients with gastric cancer. Eur J Cancer 2004;40:2260-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vickery CW, Blazeby JM, Conroy T, et al. Development of an EORTC disease-specific quality of life module for use in patients with gastric cancer. Eur J Cancer 2001;37:966-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Garland SN, Pelletier G, Lawe A, et al. Prospective evaluation of the reliability, validity, and minimally important difference of the functional assessment of cancer therapy-gastric (FACT-Ga) quality-of-life instrument. Cancer 2011;117:1302-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Woo A, Fu T, Popovic M, et al. Comparison of the EORTC STO-22 and the FACT-Ga quality of life questionnaires for patients with gastric cancer. Ann Palliat Med 2016;5:13-21. [PubMed]

- R Development Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2016.

- Siegel S. Estatística não-paramétrica para ciências do comportamento. Porto Alegre: Artmed, 2006.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Gastric Cancer Version 2. Accessed June 12, 2018. Available online: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/gastric.pdf

- Antonakis PT, Ashrafian H, Isla AM. Laparoscopic gastric surgery for cancer: Where do we stand? World J Gastroenterol 2014;20:14280-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Saito T, Kurokawa Y, Takiguchi S, et al. Current status of function-preserving surgery for gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2014;20:17297-304. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2014 (ver. 4). Gastric Cancer 2017;20:1-19. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Li Z, Fan B, Shan F, et al. Gastrectomy in comprehensive treatment of advanced gastric cancer with synchronous liver metastasis: A prospectively comparative study. World J Surg Oncol 2015;13:212. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Terwee CB, Prinsen CA, Ricci Garotti MG, et al. The quality of systematic reviews of health-related outcome measurement instruments. Qual Life Res 2016;25:767-79. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Straatman J, van der Wielen N, Joosten PJ, et al. Assessment of patient-reported outcome measures in the surgical treatment of patients with gastric cancer. Surg Endosc 2016;30:1920-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Suk H, Kwon OK, Yu W. Preoperative quality of life in patients with gastric cancer. J Gastric Cancer 2015;15:121-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Maruyama K, Gunven P, Okabayashi K, et al. Lymph node metastases of gastric cancer. General pattern in 1931 patients. Ann Surg 1989;210:596-602. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sun Z, Zhu GL, Lu C, et al. The impact of N-ratio in minimizing stage migration phenomenon in gastric cancer patients with insufficient number or level of lymph node retrieved: Results from a Chinese mono-institutional study in 2159 patients. Ann Oncol 2009;20:897-905. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nelen SD, Heuthorst L, Verhoeven RHA, et al. Impact of centralizing gastric cancer surgery on treatment, morbidity, and mortality. J Gastrointest Surg 2017;21:2000-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Luna A, Rebasa P, Montmany S, et al. Learning curve for d2 lymphadenectomy in gastric cancer. ISRN Surg 2013;2013:508719.

- Kodera Y. Extremity in surgeon volume: Korea may be the place to go if you want to be a decent gastric surgeon. Gastric Cancer 2016;19:323-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chen T, Yan D, Zheng Z, et al. Evolution in the surgical management of gastric cancer: Is extended lymph node dissection back in vogue in the USA? World J Surg Oncol 2017;15:135. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim AR, Cho J, Hsu YJ, et al. Changes of quality of life in gastric cancer patients after curative resection: A longitudinal cohort study in Korea. Ann Surg 2012;256:1008-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McCall MD, Graham PJ, Bathe OF. Quality of life: A critical outcome for all surgical treatments of gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2016;22:1101-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wu CW, Chiou JM, Ko FS, et al. Quality of life after curative gastrectomy for gastric cancer in a randomised controlled trial. Br J Cancer 2008;98:54-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Park S, Chung HY, Lee SS, et al. Serial comparisons of quality of life after distal subtotal or total gastrectomy: What are the rational approaches for quality of life management? J Gastric Cancer 2014;14:32-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Huang CC, Lien HH, Wang PC, et al. Quality of life in disease-free gastric adenocarcinoma survivors: Impacts of clinical stages and reconstructive surgical procedures. Dig Surg 2007;24:59-65. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Takiguchi S, Yamamoto K, Hirao M, et al. A comparison of postoperative quality of life and dysfunction after Billroth I and Roux-en-Y reconstruction following distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer: Results from a multi-institutional RCT. Gastric Cancer 2012;15:198-205. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kauppila JH, Ringborg C, Johar A, et al. Health-related quality of life after gastrectomy, esophagectomy, and combined esophagogastrectomy for gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma. Gastric Cancer 2018;21:533-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Takahashi M, Terashima M, Kawahira H, et al. Quality of life after total vs distal gastrectomy with Roux-en-Y reconstruction: Use of the postgastrectomy syndrome assessment scale-45. World J Gastroenterol 2017;23:2068-76. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Díaz De Liaño A, Martinez FO, Ciga MA, et al. Impact of surgical procedure for gastric cancer on quality of life. Br J Surg 2003;90:91-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kong H, Kwon OK, Yu W. Changes of quality of life after gastric cancer surgery. J Gastric Cancer 2012;12:194-200. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Munene G, Francis W, Garland SN, et al. The quality of life trajectory of resected gastric cancer. J Surg Oncol 2012;105:337-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee SS, Chung HY, Yu W. Quality of life of long-term survivors after a distal subtotal gastrectomy. Cancer Res Treat 2010;42:130-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Avery K, Hughes R, McNair A, et al. Health-related quality of life and survival in the 2 years after surgery for gastric cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol 2010;36:148-54. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Karanicolas PJ, Graham D, Gonen M, et al. Quality of life after gastrectomy for adenocarcinoma: A prospective cohort study. Ann Surg 2013;257:1039-46. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Smolskas E, Lunevicius R, Samalavicius NE. Quality of life after subtotal gastrectomy for gastric cancer: Does restoration method matter? - A retrospective cohort study. Ann Med Surg (Lond) 2015;4:371-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yang K, Zhang WH, Liu K, et al. Comparison of quality of life between Billroth-I and Roux-en-Y anastomosis after distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer: A randomized controlled trial. Sci Rep 2017;7:11245. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yu W, Park KB, Chung HY, et al. Chronological changes of quality of life in long-term survivors after gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Cancer Res Treat 2016;48:1030-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Catarci M, Berlanda M, Grassi GB, et al. Pancreatic enzyme supplementation after gastrectomy for gastric cancer: A randomized controlled trial. Gastric Cancer 2018;21:542-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lim HS, Cho GS, Park YH, et al. Comparison of quality of life and nutritional status in gastric cancer patients undergoing gastrectomies. Clin Nutr Res 2015;4:153-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sadighi S, Mohagheghi MA, Montazeri A, et al. Quality of life in patients with advanced gastric cancer: A randomized trial comparing docetaxel, cisplatin, 5-FU (TCF) with epirubicin, cisplatin, 5-FU (ECF). BMC Cancer 2006;6:274. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Climent M, Munarriz M, Blazeby JM, et al. Weight loss and quality of life in patients surviving 2 years after gastric cancer resection. Eur J Surg Oncol 2017;43:1337-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Park KB, Park JY, Lee SS, et al. Impact of body mass index on the quality of life after total gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Cancer Res Treat 2018;50:852-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Huang DD, Ji YB, Zhou DL, et al. Effect of surgery-induced acute muscle wasting on postoperative outcomes and quality of life. J Surg Res 2017;218:58-66. [Crossref] [PubMed]