Splenectomy is an independent risk factor for poorer perioperative outcomes after cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy: an analysis of 936 procedures

Introduction

Cytoreductive surgery combined with hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (CRS/HIPEC) is a potentially curative treatment for select patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis. This combined approach has consistently demonstrated improved survival outcomes across a variety of disease types including colorectal cancer, peritoneal mesothelioma, and peritoneal mesothelioma (1-3). There is randomized evidence demonstrating the superiority of CRS-HIPEC for colorectal cancer peritoneal carcinomatosis (2).

This treatment, however, has been associated with a high rate of perioperative mortality and morbidity compared to other gastrointestinal surgeries. A critical appraisal of the literature shows that in-hospital mortality varies widely across institutions between 0–17% (4). In high volume institutions, however, CRS/HIPEC is relatively safe with a reported mortality of 0–5.8% (4). The rate of grade III/IV morbidity ranges from 12–52% in high volume centers (4-6). Given the need to optimize outcomes and improve patient selection several studies have identified factors which are associated with a poorer peri-operative outcomes. It is widely acknowledged that the volume of disease, extent of cytoreduction and length of operation are associated with a poorer peri-operative outcome (5-7). Few studies, however, have evaluated the impact of specific procedures on peri-operative outcomes.

Splenectomy is relatively common procedure during CRS/HIPEC performed in up to 50% of patients in high-volume institutions (5,8). It is usually performed due to tumor involvement of the spleen or iatrogenic trauma during dissection in the left upper quadrant. Inadvertent splenectomy during other gastrointestinal surgical procedures has been associated with a higher rate of perioperative morbidity and infections complications (9-12). Moreover, splenectomy may compromise long term survival outcomes and increase the risk of developing new solid and hematologic malignancies (10,13,14). To our knowledge, only one small study has addressed the impact of splenectomy on peri-operative outcomes after CRS/HIPEC (8). The primary aim of this study was to evaluate the independent impact of splenectomy on mortality and morbidity outcomes in a large number of patients treated at a high-volume institution by a single surgeon.

Methods

The institutional review committee deems retrospective analysis of the prospectively maintained St George Hospital Peritoneal Malignancy Program Dataset to be of low-negligible risk. This is because they involve a review of de-identified data which patients had agreed to provide prior to surgery. From September 1996 to December 2015, 936 consecutive patients who underwent CRS/HIPEC by a single surgical team at St George Hospital, Sydney, Australia, were identified from a prospective database and analyzed. Selection of suitable patients for this procedure was based on the extent of disease and ability to achieve a complete cytoreduction, performance status and comorbidities. Patients who had a splenectomy during their cytoreductive procedure were identified. A case control group of similar patients, without splenectomy, was selected from the same database.

The extent of peritoneal disease was calculated and recorded using the peritoneal carcinomatosis index (PCI) as described by Jacquet and Sugarbaker (15). CRS/HIPEC was performed according to the Sugarbaker technique (16). The completeness of cytoreduction was recorded as previously described (15).

Operation reports were analyzed for the number of operative procedures performed. Demographic data, tumor characteristics, operative and postoperative details were extracted from the database and postoperative complications were graded according to the Clavien-Dindo Classification (17). All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS® (Windows Version 22, IBM Corporation, New York, USA). Patient characteristics were reported using frequency and descriptive analyses. Comparison of normally distributed variables was performed using the unpaired t-test. Categorical variables were analyzed using the Chi-square test (or Fisher’s exact test when conditions for Chi square were not fulfilled). Hospital mortality was defined as death that occurred during the same admission for CRS/HIPEC. Univariate analysis for complications was performed using Chi square tests or Fisher’s exact test, where appropriate. Multivariate analyses were performed using a binary logistic regression model. The significance level was set at 0.05.

Results

Patient characteristics

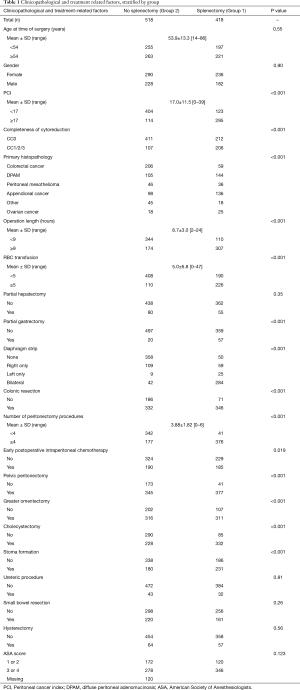

A thorough summary of patient characteristics is provided in Table 1. Overall, 418 (45%) patients underwent splenectomy (Group 1). Five hundred and eighteen (55%) patients did not undergo splenectomy (Group 2). Five hundred and twenty six (56%) patients were female. The mean age of patients at the time of surgery was 53.9±13.3 (range, 14–86) years. The mean PCI of patients was 17.0±11.5 (range, 0–39). The histopathology of the primary tumor was colorectal cancer in 265 (28%) patients, diffuse peritoneal adenomucinosis (DPAM) in 249 (27%), peritoneal mesothelioma in 82 (9%), appendiceal cancer in 234 (25%), ovarian cancer in 43 (5%) and other malignancies in 63 (7%). The completeness of cytoreduction was CC0 in 619 (67%) patients, CC1 in 267 (29%), CC2 in 41 (4%) and CC3 in 3 (0%). The mean number of peritonectomy procedures performed was 3.88±1.82 (0–6).

Full table

Table 1 demonstrates the differences in the baseline characteristics between patients in Group 1 and 2, respectively. Patients in Group 1 generally had a higher PCI (P<0.001) and consequently underwent longer procedures (P<0.001) with more peritonectomy procedures performed (P<0.001). Group 1 patients were more likely to undergo other procedures including colonic resection (P<0.001), partial gastrectomy (P<0.001) and diaphragmatic stripping (P<0.001).

Impact of splenectomy on perioperative outcomes

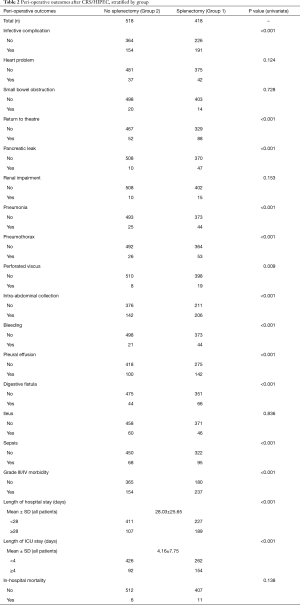

The mortality rate in the entire series was 1.8%. Table 2 stratifies perioperative outcomes based on group. On univariate analysis, patients in Group 1 were more likely to develop infective complications (46% vs. 30%, P<0.001), pancreatic leak (11% vs. 2%, P<0.001), pneumonia (11% vs. 5%, P<0.001), pneumothorax (13% vs. 5%, P<0.001), perforated viscus (5% vs. 2%, P<0.001), intra-abdominal collection (49% vs. 27%, P<0.001), bleeding (11% vs. 4%, P<0.001), digestive fistula (16% vs. 8%, P<0.001) and sepsis (23% vs. 13%, P<0.001). Group 1 patients were more likely overall to develop grade III/IV morbidity (57% vs. 30%, P<0.001). They were more likely to have a long hospital stay (≥28 days) (45% vs. 21%, P<0.001) and long intensive care unit (ICU) stay (≥4 days) (37% vs. 18%, P<0.001). Group 1 was not associated with in-hospital mortality (3% vs. 1%, P=0.138).

Full table

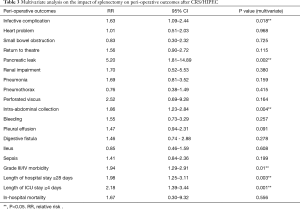

Table 3 summarizes the results of multivariate analysis evaluating the impact of splenectomy on peri-operative outcomes. Splenectomy was independently associated with a higher risk of infective complications [relative risk (RR), 1.63; 95% confidence interval (CI), 1.09–2.44; P=0.018], pancreatic leak (RR, 5.2; 95% CI, 1.81–14.89, P=0.002), intra-abdominal collection (RR, 1.86; 95% CI, 1.23–2.84, P=0.004), and grade III/IV morbidity (RR, 1.94; 95% CI, 1.29–2.91; P=0.01). It was also an independent risk factor for long hospital stay (≥28 days) (RR, 1.98; 95% CI, 1.25–3.11; P=0.003) and long ICU stay (≥4 days) (RR, 2.18; 95% CI, 1.39–3.44, P=0.001).

Full table

Discussion

Our study demonstrates that splenectomy is an independent risk factor for poorer peri-operative outcome after CRS/HIPEC. Even after accounting for confounding factors, patients undergoing splenectomy were twice as likely to develop grade III/IV morbidity (57% vs. 30%; RR, 1.94; P<0.001). This could be attributed in part to the fact that these patients were 63% more likely to develop infection and 86% more likely to develop an intra-abdominal collection.

Splenectomy was also associated with a fivefold increase in the risk of pancreatic leak (11% vs. 2%, P=0.002). This reflects the fact that splenectomy involves extensive dissection around the pancreatic tail increasing the incidence of inadvertent pancreatic injury. The poorer peri-operative outcomes meant that splenectomy patients were twice as likely to have a prolonged hospital stay (≥28 days, P=0.003) and ICU stay (≥4 days, P=0.001). Reassuringly, however, splenectomy was not associated with an increased risk of in-hospital mortality (3% vs. 1%, P=0.556).

Some of the differences observed reflect the significant differences between the two groups. Indeed, of the 19 peri-operative variables assessed, splenectomy was associated with an increased incidence of 15 on univariate analysis but only 6 on multivariate analysis. Consistent with previous series, we demonstrated that splenectomy patients have a higher disease burden and require a more extensive cytoreduction (8). In this series, 71% of patients undergoing splenectomy had a PCI ≥17 compared to only 22% in those who did not. Splenectomy patients were more likely to have undergo procedures such as diaphragmatic stripping (P<0.001), colonic resection (P<0.001) and stoma formation (P<0.001). Operation length, a surrogate marker for surgical complexity was significantly longer in the splenectomy group (<0.001). Moreover, these patients were more likely to intra-operative receive massive blood transfusion (≥5 units, P<0.001). Undoubtedly, splenectomy patients constitute a group with higher disease burden. Nevertheless, our data suggests that the addition of splenectomy to long and complex procedures such as CRS/HIPEC further increases morbidity risk.

Only one small study has addressed the impact of splenectomy on peri-operative outcomes after CRS/HIPEC. Dagbert and colleagues (8) performed a case control study of 61 patients who underwent CRS/HIPEC over a 3-year period; 30 (49%) had a splenectomy. The authors demonstrated that patients in the splenectomy group experienced more grade 3–4 complications than those in the control group (59% vs. 35.9%, P=0.041) as well as more pulmonary complications (41% vs. 7.7%, P=0.006). Splenectomy was the only predictor of grade 3–4 complications on multivariate analysis (risk ratio, 2.57; 95% CI, 1.03–6.40). There was no difference in mortality between the two groups. The authors did not show an independent association of splenectomy with infective complications; this, however, may reflect the small number of patients in the study.

Unplanned splenectomy has been consistently associated with poorer perioperative outcomes in patients undergoing other types of intra-abdominal surgery. Mettke and colleagues (9) performed a prospective multicentre study of 46,682 patients who underwent resection for colorectal carcinoma between 2000 and 2004. Of these, 640 (1.4%) suffered an iatrogenic splenic injury during surgery necessitating either removal or repair. The authors demonstrated that splenectomy increased both morbidity (47.2% vs. 36.5%, P=0.003) and mortality (11.8% vs. 3.1%, P<0.001). Anastomotic leaks requiring surgery were observed most frequently following splenectomy (7.9%) but this was significantly lower following spleen preservation (3.3%, P=0.003). An association of splenectomy with impaired anastomotic healing has been reported in animal studies and may explain the increased risk of peri-operative morbidity that we observed (18). Wang and colleagues (10) evaluated 4,323 patients who underwent nephrectomy at Mayo clinic between 1992 and 2008; 33 (0.8%) had an unplanned splenectomy. Consistent with the results of our study, patients with unplanned splenectomy had longer operative times (205 vs. 171 min; P=0.02), higher estimated blood loss (1.3 vs. 0.3 L; P=0.001), longer length of stay (median 7 vs. 5 days; P=0.03) and a greater incidence of peri-operative morbidity (RR 5.3; P=0.002). Similar outcomes have been reported for esophageal and gastric cancer surgery (11,12).

There is an immunological basis for the increased morbidity observed in patients undergoing splenectomy. The spleen functions as a phagocytic filter which removes damaged cells, eliminates blood-borne microbes and also producing antibiotics (19). Consistent with the results of this study, there is a definitive association between asplenia and increased morbidity and mortality from infectious etiologies (20). Overwhelming postsplenectomy sepsis (OPSS) is a significant concern in the asplenic patient and occurs in in 0.05% to 2% of splenectomized patients (21). This is related to the increased risk of infection by encapsulated organisms, most commonly by Streptococcus pneumonia, both also haemophilus influenza and Neisseria meningitides (22). This has led to the knowledge that splenectomised patients should be vaccinated to decrease the risk of OPSS due to organisms (19). In our institution, all patients, whenever possible, are vaccinated 2 weeks before the operation in order to allow patients to create antibodies and prevent OPSS.

In the context of CRS/HIPEC, splenectomy is most commonly performed for tumor implantation. In this case, spleen preservation is only possible when there is minor splenic involvement, particularly in mucinous tumors. Partial spleen capsulectomy can be effectively performed for limited disease (8). Iatrogenic splenic injury is another common cause of splenectomy. As discussed by Dagbert and colleagues (8), intraoperative splenic injury may be the result of inferior pole avulsion during mobilization of the splenic flexure of the colon or from aggressive retractor placement on the greater omentum during completion omentectomy. Limiting traction on the omentum is pertinent to reducing the risk of inadvertent splenic injury. Moreover, careful dissection when undertaking adjunct procedures such as stripping of the left diaphragm maximizes the likelihood of spleen conservation. When inadvertent splenic injury occurs, there are some potential therapeutic options. Electrocautery can be used but it may exacerbate the existing injury. There have been promising reports on the use of topical fibrin sealant and surgical adhesive to the laceration site (10,23). These warrant further exploration in the setting of CRS/HIPEC. Splenorrhaphy, utilizing pledgeted sutures, mesh and topical hemostatic agents has been used to good effect in the trauma setting (24). Nevertheless, splenic repair is not always successful and many patients initially considered suitable for spleen salvage will subsequently require splenectomy (25).

Our study is by far the largest to evaluate the impact of splenectomy on outcomes after CRS/HIPEC. Nevertheless, it has several limitations. Firstly, it is an observational, retrospective study from a single high volume institution. The results from this study may not necessarily translate into those observed at other centers. Moreover, limitations inherent to a retrospective study design also apply to this study. Secondly, potential confounding from unknown variables may have affected the analyses. In particular, it must be noted that patients undergoing splenectomy generally underwent a more extensive cytoreductive procedure. Although we accounted for adjunct procedures and the extent of cytoreduction, unknown variables could have influenced outcomes. Thirdly, whilst this is by far the largest study to examine the impact of splenectomy on peri-operative outcomes, it may not be sufficiently powered to demonstrate an association with low event rate complications such as in-hospital mortality. Nevertheless, this study shows with significant conviction that splenectomy independently confers a poorer peri-operative outcome.

In conclusion, splenectomy is an independent risk factor for poorer peri-operative outcomes including grade III/IV complications, infection and pancreatic leak. Minimizing the likelihood of inadvertent splenic injury through careful dissection and routine vaccination of CRS/HIPEC patients prior to surgery can improve outcomes. Spleen-conserving surgery in the presence of limited metastatic involvement should also be considered.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical statement: The study was approved by institutional ethics committee of St George Hospital.

References

- Yan TD, Deraco M, Baratti D, et al. Cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy for malignant peritoneal mesothelioma: multi-institutional experience. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:6237-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Verwaal VJ, van Ruth S, de Bree E, et al. Randomized trial of cytoreduction and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy versus systemic chemotherapy and palliative surgery in patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis of colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 2003;21:3737-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chua TC, Moran BJ, Sugarbaker PH, et al. Early- and long-term outcome data of patients with pseudomyxoma peritonei from appendiceal origin treated by a strategy of cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:2449-56. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chua TC, Yan TD, Saxena A, et al. Should the treatment of peritoneal carcinomatosis by cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy still be regarded as a highly morbid procedure?: a systematic review of morbidity and mortality. Ann Surg 2009;249:900-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Saxena A, Yan TD, Chua TC, et al. Critical assessment of risk factors for complications after cytoreductive surgery and perioperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy for pseudomyxoma peritonei. Ann Surg Oncol 2010;17:1291-301. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Glehen O, Gilly FN, Boutitie F, et al. Toward curative treatment of peritoneal carcinomatosis from nonovarian origin by cytoreductive surgery combined with perioperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy: a multi-institutional study of 1,290 patients. Cancer 2010;116:5608-18. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mizumoto A, Canbay E, Hirano M, et al. Morbidity and mortality outcomes of cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy at a single institution in Japan. Gastroenterol Res Pract 2012;2012:836425. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dagbert F, Thievenaz R, Decullier E, et al. Splenectomy Increases Postoperative Complications Following Cytoreductive Surgery and Hyperthermic Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy. Ann Surg Oncol 2016;23:1980-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mettke R, Schmidt A, Wolff S, et al. Spleen injuries during colorectal carcinoma surgery. Effect on the early postoperative result. Chirurg 2012;83:809-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang JK, Tollefson MK, Kim SP, et al. Iatrogenic splenectomy during nephrectomy for renal tumors. Int J Urol 2013;20:896-902. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kyriazanos ID, Tachibana M, Yoshimura H, et al. Impact of splenectomy on the early outcome after oesophagectomy for squamous cell carcinoma of the oesophagus. Eur J Surg Oncol 2002;28:113-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Galizia G, Lieto E, De Vita F, et al. Modified versus standard D2 lymphadenectomy in total gastrectomy for nonjunctional gastric carcinoma with lymph node metastasis. Surgery 2015;157:285-96. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wakeman CJ, Dobbs BR, Frizelle FA, et al. The impact of splenectomy on outcome after resection for colorectal cancer: a multicenter, nested, paired cohort study. Dis Colon Rectum 2008;51:213-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kristinsson SY, Gridley G, Hoover RN, et al. Long-term risks after splenectomy among 8,149 cancer-free American veterans: a cohort study with up to 27 years follow-up. Haematologica 2014;99:392-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jacquet P, Sugarbaker PH. Clinical research methodologies in diagnosis and staging of patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis. Cancer Treat Res 1996;82:359-74. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sugarbaker PH. Peritonectomy procedures. Ann Surg 1995;221:29-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg 2004;240:205-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Karip B, Mestan M, Isik O, et al. A solution to the negative effects of splenectomy during colorectal trauma and surgery: an experimental study on splenic autotransplantation to the groin area. BMC Surg 2015;15:129. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Di Sabatino A, Carsetti R, Corazza GR. Post-splenectomy and hyposplenic states. Lancet 2011;378:86-97. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- William BM, Thawani N, Sae-Tia S, et al. Hyposplenism: a comprehensive review. Part II: clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and management. Hematology 2007;12:89-98. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shatz DV. Vaccination practices among North American trauma surgeons in splenectomy for trauma. J Trauma 2002;53:950-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bisharat N, Omari H, Lavi I, et al. Risk of infection and death among post-splenectomy patients. J Infect 2001;43:182-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Olmi S, Scaini A, Erba L, et al. Use of fibrin glue (Tissucol) as a hemostatic in laparoscopic conservative treatment of spleen trauma. Surg Endosc 2007;21:2051-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Feliciano DV, Spjut-Patrinely V, Burch JM, et al. Splenorrhaphy. The alternative. Ann Surg 1990;211:569-80; discussion 80-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Holubar SD, Wang JK, Wolff BG, et al. Splenic salvage after intraoperative splenic injury during colectomy. Arch Surg 2009;144:1040-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]